Saddiq Dzukogi walked, images of the world making lines of poetry on the pages of his notebook. Vague memories of Minna, Nigeria, float back – roasted yam with palm oil, farmers threshing rice husk during harvest. Cars and faces streamed past as he walked the bicycle paths of Lincoln, Nebraska, sometimes walking more than eight miles a day into the underbelly of the city.

As he walked through Noxubee Wildlife Refuge, he stopped to chat with two lovers in the throes of nostalgia. Alone again in an isolated grove, he allowed himself to be immersed in the music of the wind blowing through branches as birds sang overhead.

“I’m just training myself to pay attention to all of those wonderful things happening and trying to preserve – even if it’s just a little of those moments – for someone else to interact with,” Dzukogi said.

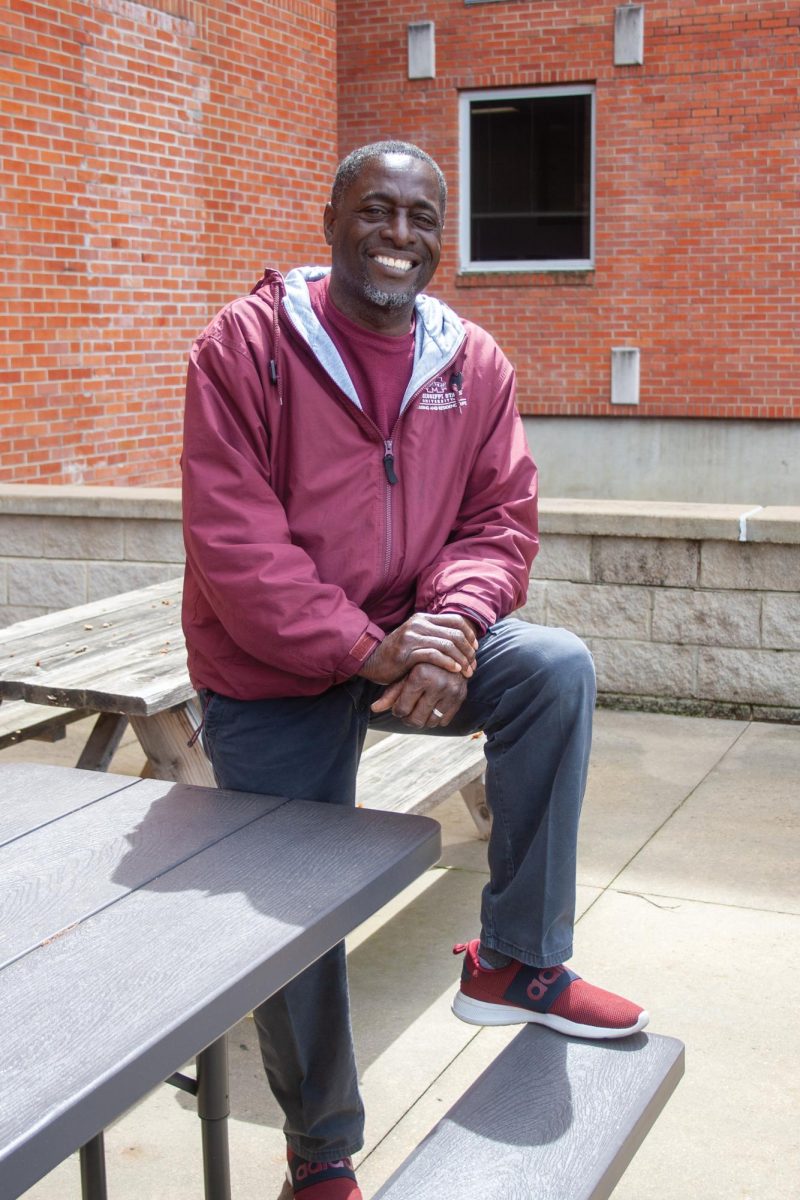

Dzukogi, an assistant professor in Mississippi State University’s Department of English since 2022, has found purpose in equipping students with the skills he has used to be present in life.

“There is nobody that can sing about your life better than you, right? It’s more genuine and authentic because if you’re transmitting your stories for someone else to provide, there will be a lot of things missing in that transmission,” Dzukogi said. “Because, at best, they would be doing the work of translating. Even if it’s still English, it is translating because they do not have the context that you have.”

Saddiq grew up in the vibrant culture of his native Minna, a place his father called “the valley of poets.” After he studied mass communication at Ahmadu Bello University in Zaria, Nigeria, he decided he was committed to improving the craft of storytelling. Six years ago, Dzukogi received a scholarship to study for a doctorate in English at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

“The thing was, moving far away from home, you’re in a perpetual loop of nostalgia. I’m walking the street smelling trees to ascertain if it smells like the leaves back home. There is that acute awareness of home when you’re far away. I’ve gotten better at handling it, but it’s still there.”

Dzukogi’s connection to Nigeria has remained strong – much of his work seeks to examine the connections between the places he calls home.

“I think the greatest influence Nebraska had on me was appreciating where I come from. I didn’t realize I was the poet of my people until I lived in Nebraska away from my people. And I started thinking about it more closely; I started thinking about the history and what that means to me. I had a more intimate look at home by virtue of the distance,” Dzukogi said.

As a Nigerian immigrant, Dzukogi initially saw himself outside the African American experience. Since he arrived in Mississippi, he has allowed himself to reconsider this experience in his work.

“It’s like all of the voices of all of those people all those years ago are asking for me to be in conversation with them, and I’m beginning to look at Blackness from a more global point of view. There was a day I was talking to somebody; I didn’t even catch their name. But I was talking about this anxiety to engage African American culture, even as a Black person from Africa, living here, who’s now in a way at least a witness of what that means and also large ways a participant. He said the most beautiful thing, and that was so freeing, ‘A fish on a tree is not a bird, it’s still a fish,’” Dzukogi said.

“And what that means is: all those people who were taken, you know, like from Africa all those years ago, regardless of where they are, they’re still my people. It’s a different history now; they’ve had different experiences now. But they were taken from Africa – me, too, right? Being here has afforded me the opportunity to kind of reconnect to that lineage and examine it from the point of view of an outsider, but also somebody who can trace some lineage to those people,” Dzukogi said.

Dzukogi said that raising a young Black family in Mississippi has given him a unique perspective on heritage. Dzukogi’s son Farid, aged 5, is one of three siblings and was born in Nebraska.

“I started thinking, I’m also contributing to a culture that is American, to a kind of Blackness that is American, because my son – he’s an American. It’s weird – I’m still trying to understand what that means. If he’s thinking about home, he’s thinking about Lincoln, Nebraska, and if I’m thinking about home, I’m thinking about Nigeria. There’s like intersection and roots and it’s fascinating to have all of that and to learn from it,” Dzukogi said. “… just observing that is enriching; it’s beautiful; it’s confusing and it’s a gift just to see all of that unfold because it allows me to think about others, and to think about ways that we’re all similar, even though we might think there’s difference by the things that we decide to call ourselves.”

Working towards his Ph.D. at Nebraska-Lincoln on a graduate student stipend, Dzukogi struggled to support his wife and children. He reached out to multiple universities for a professorship, a way he felt he could use the craft of storytelling to make a positive impact.

“My dad used to tell us, ‘It’s easier to bend a fish before it dries.’ If it dries and you bend it, it’ll break,” Dzukogi said. “… Young people have more stake in the future. And if you want that future to be great, you have to find a way to shape those would-be leaders of that future in a way that they will be conscious of themselves and others and great stakeholders that would care about that future.”

Callie Matthews, a senior majoring in psychology with a minor in creative writing, had a childhood passion for creative writing – something that fell out of focus after she was consumed with her studies at MSU. After two classes with Dzukogi, Matthews said that his laid-back teaching style fostered organic creative expression.

“In college, you don’t always feel like you have a good place to express yourself and contribute creatively, especially if you’re not an art major. You know, getting bogged down in a lot of other work and then also just life being difficult at times,” Matthews said. “So, I had stopped writing poetry as frequently as I used to, and I feel like taking his class for the first time kind of reignited my inspiration to write and use poetry as something like a place where I can express my personal thoughts or feelings and observations.”

Matthews maintains a connection with Dzukogi and said she appreciates his help in helping her make her creative journey. She hopes to publish a collection of poems in the future and hopes to utilize creative writing in her future career as a professional counselor.

“One thing I would eventually like to do is maybe like start an organization on the side or something where young people could write together and find a safe space with other artists,” Matthews said. “Because it’s proven that after you encounter a situation that causes you grief or is traumatic, if you write about it, it’s effective for you to overcome it in similar ways as giving therapy.”

Olufunke Ogundimu, an assistant professor in the Department of English from Lagos, Nigeria, studied alongside Dzukogi at Nebraska-Lincoln. There, Dzukogi’s family was a community. If Ogundimi needed help, he was there. She fondly remembers his family hosting a birthday party for her. Saddiq’s wife cooked samosas and buttered crabs, and she went home with a drawing from one of his children.

Dzukogi helped convince Ogundimu to make her way to MSU, a place she believes is uniquely receptive to alternative viewpoints. She and Dzukogi serve as soundboards for each other’s creative works.

“As a social being, you need someone that you can trust enough with your work, that would give you effective feedback, and constructive feedback. I know that it’s coming from a place of respect and love, they’re not trying to pull you down,” Ogundimu said.

Ogundimu said Saddiq’s presence on campus is a unique opportunity for students interested in improving the craft of storytelling.

“A lot of times we read about poets who have departed and all of that, but to be able to ask questions to a living, writing, productive, critically acclaimed poet is really important,” Ogundimu said. “… Sometimes, there’s a lot of myth surrounding the creation of poems and poetry itself and poetics. One thing that I noticed that he does is that he removes that myth, he makes it simple, right? He makes it as simple as breathing. This is you, the poet, walking around in your neighborhood, the world is there you are in the world. Write what you see, write what you feel.”

Dzukogi said his journey so far has tested his limits, but he now feels he can reach his goals no matter how insurmountable a challenge may seem.

“I just enjoy to tell the story of my life, and the story of the places that have impacted me, the people that have impacted me,” Dzukogi said. “The goal is pure hubris, right? I want to be eternal. Life’s fleeting, and I am writing for there to be a fossil record of my existence when I leave this space. I’m all about capturing the story of life – however routine it is – because I want those stories to speak for me long after I’m gone.”

Dzukogi is best known for his collection of poems, “Your Crib, My Qibla,” which explores his grief after the death of his daughter six months before he arrived in the U.S. Dzukogi currently has three finished manuscripts and is working to produce an epic poem.

Dzukogi embraces the uncertainty of his future.

“I just want to be able to do things I love to do: write poems and talk to people about poetry,” Saddiq said. “I do not look too far into the future. I want to be present in the moment.”