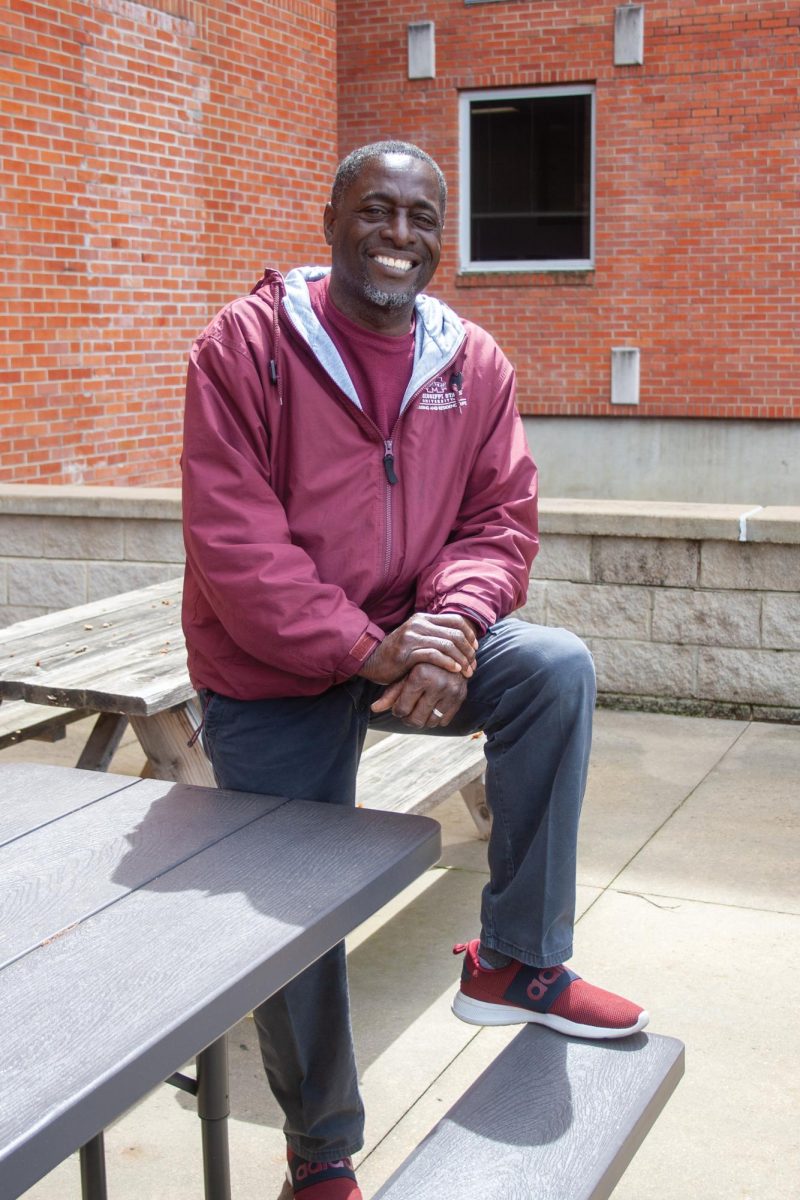

In May 2015, only a week after I sat in my residence hall watching riots unfold on the news, I began interning at the Public Defender Service for the District of Columbia. Riots had ignited the city of Baltimore and sparked debate across Mississippi State University’s campus over the issue of police brutality following Freddie Gray’s death in police custody.

Merely a week later, I found myself sitting in a D.C. office facing a bulletin board with Freddie Gray’s records pinned to it. Within a short time frame, I was exposed to two very different worlds in terms of how police brutality is discussed and understood.

I grew up in a white middle class family where more than one relative served in the police force. Growing up, I saw police as the “good guys” who wanted to protect us and helped catch the “bad guys,” like on on Law and Order.

For many individuals I know, this is the only kind of interaction or perception of police they have ever held or encountered. However, that summer, as I began my work as an intern investigator in D.C., it became clear that the debate over police brutality was far more complex than I could have imagined while sitting on my bed in Hathorn Hall.

What it is like to be on the receiving end of police brutality became more than a topic on a syllabus. I watched videos of a client whose face was bloodied by officers for no reason. I spent days in a low-income neighborhood of D.C. collecting video footage from neighbors who recorded the harsh physical interaction between officers and a client.

I met a man who lost his home and job following his arrest by an officer who failed to consider the presence of probable cause. After this man spent time in jail for charges that were eventually dropped, I watched as he attempted to rebuild his life after losing everything.

My experience that summer forever altered my side of discussions on the issue of policing. Now, over a year later, I find myself again sitting on my bed in Starkville watching news of riots unfolding—this time in Charlotte, North Carolina but in response to the same issue.

I know that for some, this topic invokes the urge to share a quick reminder that the acts of a few officers do not define the majority, and I concede this point. 2008 statistics released by the Justice Department show only 1.4 percent of individuals who had recent contact with police were threatened or experienced the use of force.

This demonstrates that actions performed in a discriminatory and abusive manner are not the norm but rather the exception. However, there is a danger in this response. The danger lies in the logic that condemning police brutality is equated with being generally “anti-police.” We must be careful not to view this as a dichotomy.

It is possible to support the work of police officers while simultaneously holding these same officers to a standard that castigates those who abuse this power. The second danger in this response is its ability to swiftly disparage the importance of the injustice movements such as Black Lives Matter aim to address.

The issue of police brutality carries with it the need to address racial disparities in how our nation’s criminal justice system functions. In 2006 the ACLU found that although blacks make up only 15 percent of the nation’s drug users, yet they make up 37 percent of those arrested and an astonishing 74 percent of drug offenders sentenced to prison.

Justice Department records show,“black drivers are 31 percent more likely to be pulled over than white drivers.” Not only are racial disparities seen in arrest rates and likelihood of being pulled over, but it is evident in an analysis by the U.S. Sentencing Commission. The analysis found prison sentences for “black men were nearly 20 percent longer than those of white men for similar crimes.”

Most unsettling of all is The Sentencing Project’s report that “1 in every 3 black males born today can expect to go to prison at some point in their life.” So when we discuss the issue of police brutality, it is imperative that we recognize these as not merely isolated incidents but as a symptom of our nation’s skewed incarceration-related state.

During my time working on cases in D.C., I was exposed to circumstances that I remained clueless to while growing up. I learned that even though you may not witness a particular reality, it does not mean it is not true for others.

While I will never be able to fully understand the heartbreak expressed by those who have personally experienced police brutality and injustice, I believe it is my responsibility to listen and take part in the solution.

If you are like me and do not have a personal experience with the issue of police brutality or have never experienced over-policing in your neighborhoods, this is what I ask: before you rush to condemn the violence occurring in Charlotte in response to the killing of Keith Lamont Scott by police, listen to what the cries demanding justice are saying. Before you revert to a never-ending debate over the intricacies of each case involving an officer’s use of lethal force, I ask you to contemplate why race remains a factor in the number of fatalities for which police are responsible.

Why, even when controlling for the racial gap in arrest rates, the Center for Policing Equity still found that force is more likely to be used against blacks than whites. I ask that you take the time to try and understand why there are riots in the street.

Then, I ask you to do something about it. Visit websites like joincampaignzero.org, where they have laid out tangible policy changes that are proven effective at addressing these issues. You can speak with your legislators on how these can be implemented.

However, at the end of these efforts, as an individual who believes in the transformative ability of effective policy reform, I find these efforts are still not enough. This is an issue that requires us all to reflect on what a criminal justice system that systematically oppresses a particular race means for the character of our society. Because as attorney Bryan Stevenson so eloquently stated, “The true measure of our character is how we treat the poor, the disfavored, the accused, the incarcerated and the condemned.”