About two weeks ago, there was an article in the Reflector titled Attendance should be optional. As a student, I understand that it is very easy to relate to an article arguing in favor of freedom from attending class.

It may have seemed like the exact story of your life—unjust professors taking away your precious points because you were not present for lectures. While I related to this article in favor of optional attendance, I also started considering different sides of the mandatory attendance issue and decided to look a little further into the issue.

Unlike what the initial article suggested, attendance is not completely and strictly enforced for every class. Within the school policies, it is possible for a student not to attend the classes and still pass all of their courses.

The AOP 12.09 Class Attendance & Reporting Absences Policy approved by Dr. Keenum clearly specifies that “passing or failing a course should not rest solely on class attendance and participation.”

Furthermore, in no part does the policy imply that students shooting for grades better than merely a passing grade must attend and participate in class. Basically, the decision for how strict or loose of an attendance policy each class has rests squarely on the shoulders of the instructor.

This sounds like a very fair policy because the instructor is the person in charge of evaluating what the students gain from the course in different ways. There is no one better than the instructor of a class to decide if attendance or participation are necessary for students to benefit from the lectures. Upon registration for a class, students nonverbally accept the instructor’s expertise in deciding what the best practice is to evaluate students’ progress and understanding of the material.

However, even when we accept this to be true, it is hard not to wonder why a stricter attendance policy is popular with most class instructors.

A quick response to this query was mentioned in the Lowe’s article—statistically, students who attend class more often perform better on tests and quizzes.

The crux of the Chris Lowe’s argument in his article lies exactly here: He correctly argues that students are adults, and they should be given the choice to decide for themselves if they think class attendance will or will not help them.

While personally I cannot deny the importance of the university providing choices for college-aged adults to learn from, I cannot deny that we tend not to make the best decisions for ourselves.

Dan Ariely, in his book Predictably Irrational, did some very interesting research that shows how students do not always choose well for themselves. In the start of one of his classes, Ariely, a professor, gave his students the choice to select an attendance policy they feel is reasonable.

He found that students whom recognized their own vulnerability to shirking work and opted for a stricter policy based on this performed the best. On the other hand, students who failed to acknowledge their aversion to attending class left themselves too much freedom, which ended up hurting their grades.

Ariely later on compares the performance of this very liberal class structure to a more dictatorial structure, where he expected attendance and submissions on pre-specified days, to find out if forcing more structure on a class leads to better performance.

While more structured classes certainly takes away students’ choices in how they go about their own learning, for students in Ariely’s class, a more deadline-based class with mandatory attendance only helped their grades.

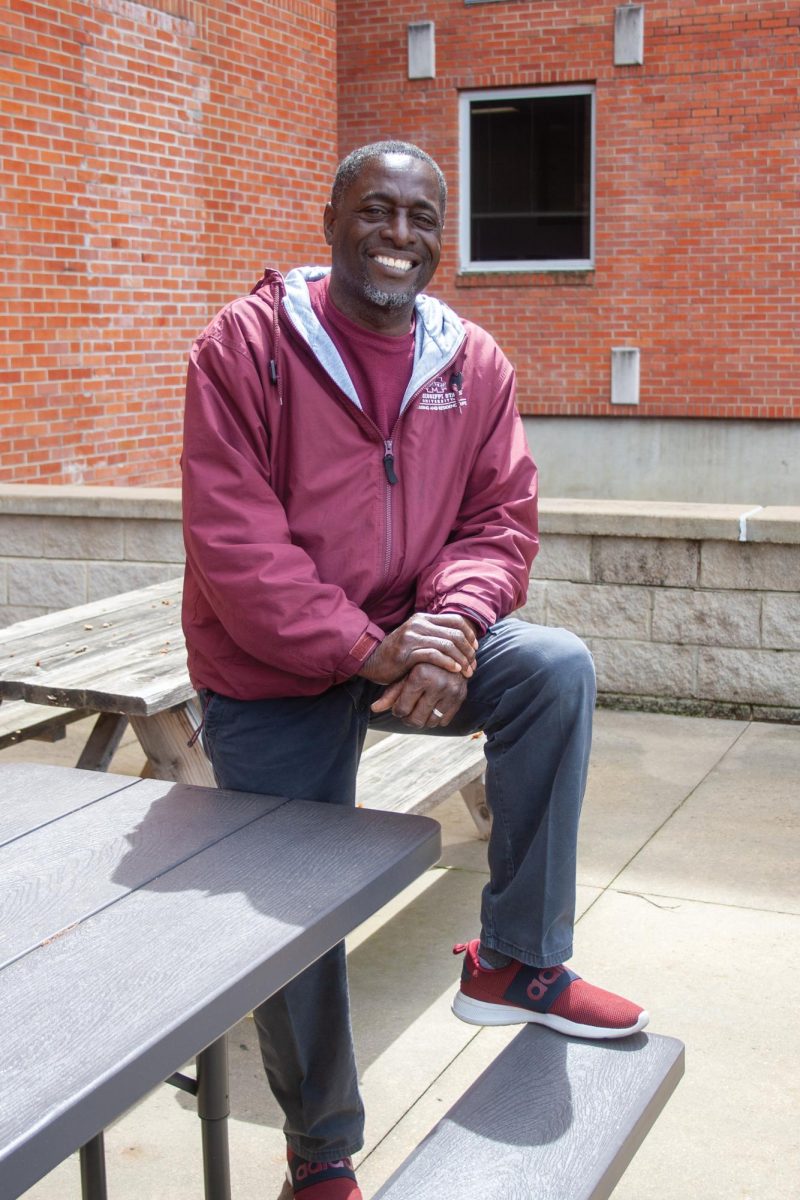

Dr. Thomas Bourgeois, dean of students, told me in casual conversation one day that a university education is not just about what you learn in class—it is also about gaining valuable life skills to help in your career. Like it or not, part of keeping your career is showing up every day.

One could argue making the right decisions for students in the form of attendance policies does not teach them to make correct decisions on their own, without added pressure.

Basically, if the university were to work under a completely liberal attendance and participation policy, the performance of the students on average would suffer; however, students who succeed in receiving a degree would be proven better at managing themselves.

I believe mandatory attendance still helps students to manage themselves—they must manage to make it to all their classes in addition to completing assignments, which prepares them for a future of showing up every day to work.

I have experienced class in universities with little to no attendance and homework policies in my home country, Iran. In Iran, most instructors do not go out of their way to restrict students so that they will perform better. Instead, there are only one or two exams, and one’s score is decided solely based on those test grades.

At the end of the day, it is easier for an instructor to worry only about one or two exams instead of trying to keep up with students’ attendance, homework assignments and quizzes.

I would state that at MSU, as well as other American universities, instructors put in more effort and energy to lead students in the right direction. They want students to achieve more in their classes. Regardless of the reasons behind this, these extra efforts merit recognition and appreciation from students.

At the campus level, AOP 12.09 Class Attendance & Reporting Absences Policy is very strong. In my mind, it walks an almost perfect line between giving instructors leeway to mold their course requirements and still making sure those attendance requirements are not too harsh on students.

While I am not presenting a hard stance on mandatory attendance either way in this article, I am simply presenting the side of the instructor in a way I feel Lowe’s attendance article did not. I felt more light could be shined on the other side of the attendance policy debate.

As it happens, I have been on both sides of this conundrum as a grad student. In different stages of my college life, I have participated in classes as both student and teacher.

As a student, I would rather take a very structured class that gives me a roadmap of what I need to do during a semester. As a teacher, I prefer to lead a semi-structured class while encouraging students to attend and participate through extra points, rather than necessary ones.