I would like to say I was surprised when I read the headline last week stating Mississippi was considering the firing squad as a method of execution, but I was not. Unfortunately, Mississippi is not the only state taking two giant leaps backward on the issue of capital punishment.

Since the sole provider of sodium thiopental– an anesthetic that is part of the cocktail used in lethal injections–stopped production in 2011, states have been scrambling to find other means of execution. As a result of this shortage, Mississippi has not had an execution since 2012, according to the Mississippi Department of Corrections.

HB 638, which passed the Mississippi House with 74 votes last week, would provide Mississippi with alternate forms of execution including the gas chamber, firing squad, and electric chair.

Additionally, the bill would prevent the names of any parties associated with the execution, including drug manufacturers, from being released to the public, because this could lead to ethical problems.

According to a Buzzfeed News report, in 2015, Texas attempted to purchase a lethal injection drug from a company in India. The state was, however, unable to do so before the Indian government raided the company, which was consisted of five 20-year-old men, producing narcotics in a small apartment.

Other states, such as Nebraska, have also attempted to illegally purchase lethal injection drugs that were not approved by the FDA.

Most importantly, the bill represents a moral departure from global progress on the issue of the death penalty. Instead of searching for new methods of execution, Mississippi leaders should remove the death penalty altogether.

The United States is currently the only developed country that still executes its citizens.

According to Amnesty International, the United States ranked 5th for most executions for 2015, sitting quite cozily between Iraq and Saudi Arabia.

The United Nations voted in 2014 for a resolution calling for a moratorium on the death penalty, but the U.S. was one of only 38 countries who opposed it. Even beyond basic support of capital punishment, the United States has lagged behind other countries on more specific aspects of capital punishment.

It was not until the 2002 Supreme Court ruling in Atkins v. Virginia that executing an intellectually disabled individual was ruled unconstitutional, or until 2005 Roper v. Simmons that sentencing a juvenile was no longer permitted, taking the U.S. nearly three decades to comply with the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.

Mississippi’s move towards expanding execution practices stands in stark contrast to the global trend on this issue.

If you are currently thinking that a global trend is not sufficient reason to alter domestic policy, then you are probably right. Which is why there are plenty of other reasons Mississippi and the United States should alter its position.

First of all, the death penalty is extremely costly. A 2011 study conducted by Federal Judge Arthur Alarcon and Loyala Law School Professor Paula Mitchell found that the death penalty had cost California taxpayers $4 billion dollars and by commuting those currently on death row to life without parole, the state would save approximately $5 billion over a 20 year period. This trend in costs holds true for other states as well.

According to the Death Penalty Information Center (DPIC), the majority of capital cases stem from only 2 percent of U.S. counties, which shifts the exorbitant cost of executions to the entire state. However, in some cases, the high cost means raising county taxes to foot the bill.

A Wall Street Journal article pointed out that in the 1990s Quitman County, Mississippi raised taxes three times, and then still took out a loan in order to pay for the capital trial of two men. When resources are spent on the death penalty, it detracts from other programs. Being a state with budget problems, Mississippi quite literally cannot afford this.

For how much we spend on the death penalty, it is severely ineffective at deterring crime.

In a 2009 survey of “former and present presidents of the country’s top academic criminological societies, 88 percent of these experts rejected the notion that the death penalty acts as a deterrent to murder. Even though the South accounts for 80 percent of executions, FBI reports still show the region has the highest murder rates.”

Many death penalty advocates argue that if we speed up the appeals process and number of executions per year, the death penalty’s general deterrence would be more effective and less costly. Or as author Edward Abbey puts it, “The death penalty would be even more effective, as a deterrent, if we executed a few innocent people more often.”

DPIC reports that there have been 157 people exonerated from death row since 1973 with the most recent occurring on January 19, 2017.

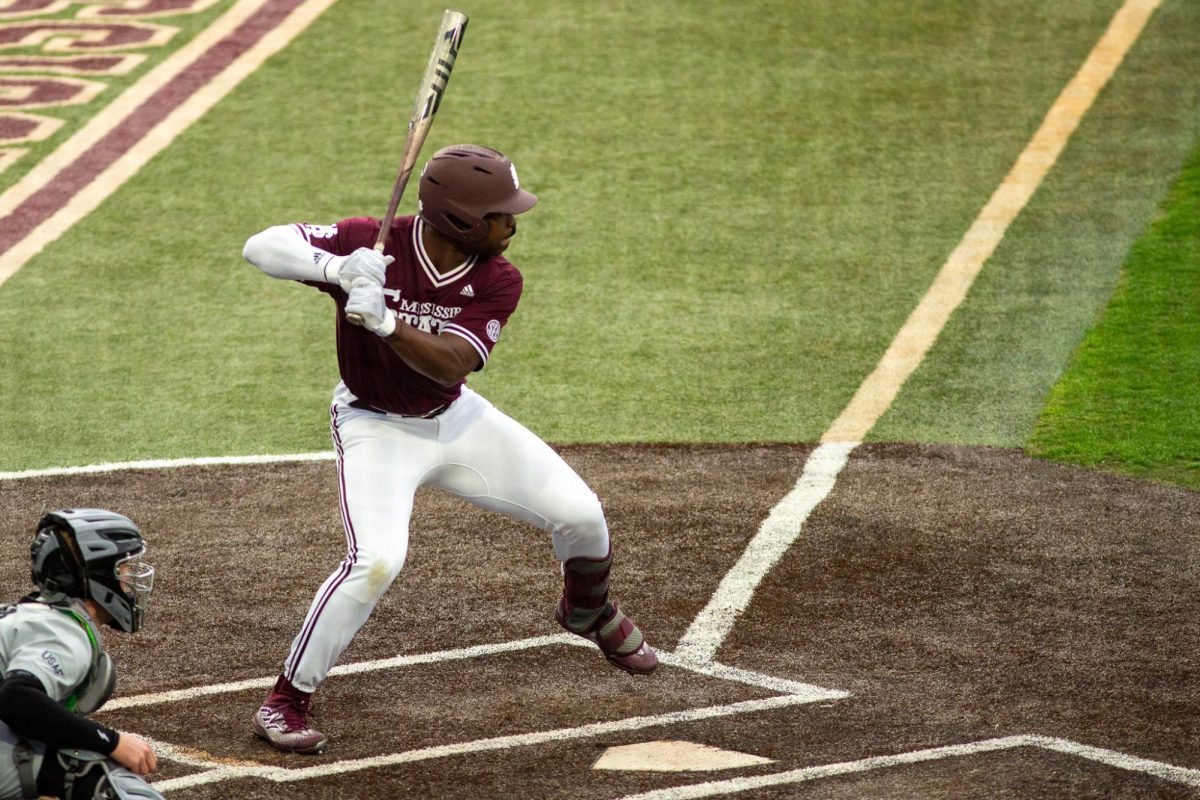

Mississippi accounts for four of these exonerations, with one being a Starkville man who was exonerated of two capital murder charges as recently as 2015. The risk of executing the innocent is simply too great. In addition, the system has proven to be racially biased.

A 1984 Stanford study found that the defendant’s odds of receiving a death sentence were 5.5 times higher if the victim were white. The ACLU reports that blacks currently account for a disproportionate 55 percent of those currently awaiting execution. By combining the global trend towards abolition with the cost, deterrence, rate of exonerations, and proven racial bias, it is compellingly clear why the United States and states such as Mississippi must also choose abolition.

Even when considering these facts, I am still often asked, “but what if it were you whose loved one was killed, wouldn’t you want the death penalty then?”

Alexis Durham responds to this in the Northwestern Law Review by asking instead this: “Should society be content to accept retributivist emotions as worthy of normative preservation and codification in law simply because such feelings have been a regular part of human reactions?” The answer is no.

Ultimately, it is a luxury to view people through only the veil of their crimes —when they have a name and story, the issue becomes more complex.

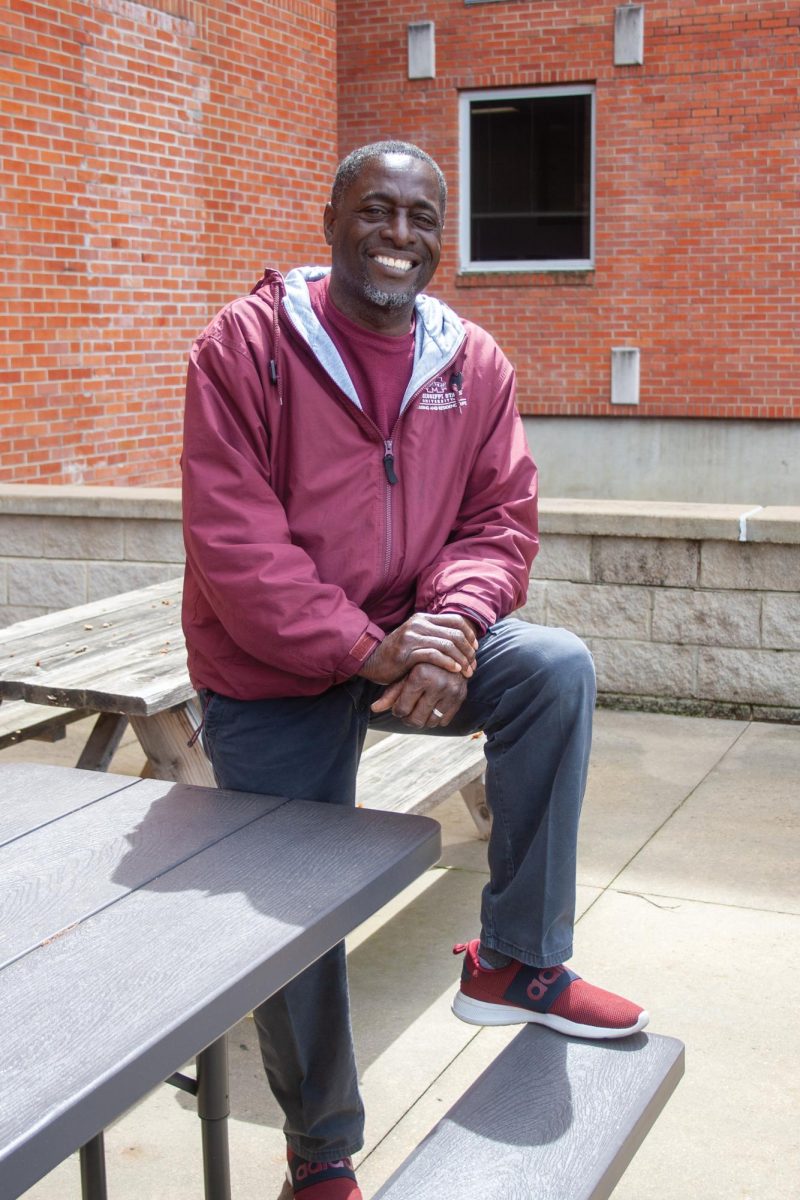

I have sat in jail across the table from individuals who were facing a looming death sentence or execution. I saw this complexity first-hand because each time I sat there, I was consistently confronted by how blatantly human they were.

When MS legislators consider what this bill will cost us, I ask that they also consider what it will cost us morally, as a state. The question they must ask is not whether people deserve to die, but rather, whether we as a state deserve to kill. The answer again is no.