Sandra Correa, aged 23, had been researching in the remote Colombian Amazon for two months. It was the rainy season of 1997. It rained and rained, and the river swelled by more than 30 feet, spilling out of the riverbanks and flooding the surrounding rainforest. This is what Correa came for — to study the fish that depended on this temporal, flooded forest to survive.

One night, Correa decided to leave her nets out after nightfall in hopes of catching more fish. Her fellow researchers had little interest in accompanying her to retrieve the nets as they promised, but she could not leave them. She only had the two, and if a black caiman destroyed them trying to get to the fish inside, completing her undergraduate thesis would be impossible.

She wolfed down some oatmeal, grabbed a flashlight and started walking the kilometer-long trail to the lakeshore’s edge. A full moon shone across the lake — the rainforest alive with the sounds of wildlife. After an hour of searching by canoe, she was lucky enough to find her nets. She heaved them aboard to find they were full of huge, black piranhas.

Correa crossed the lake as dark clouds reached across the moon. By the time she arrived back to shore, it was pitch black. The batteries in her flashlight flickered out. Crying, she carried the little 2.5 HP engine and loaded fishnet into a storeroom, locked herself inside, and fell asleep.

Correa woke in the early hours of the morning with the full moon still illuminating the trail back to the research field station. Carrying a sack of fish through the pristine heart of the Colombian Amazon, she feared a jaguar attack.

When she returned, everyone was asleep, and no one had noticed her absence. The experience forced Correa to realize her independence; it was her research, her project and her responsibility to stay alive and healthy.

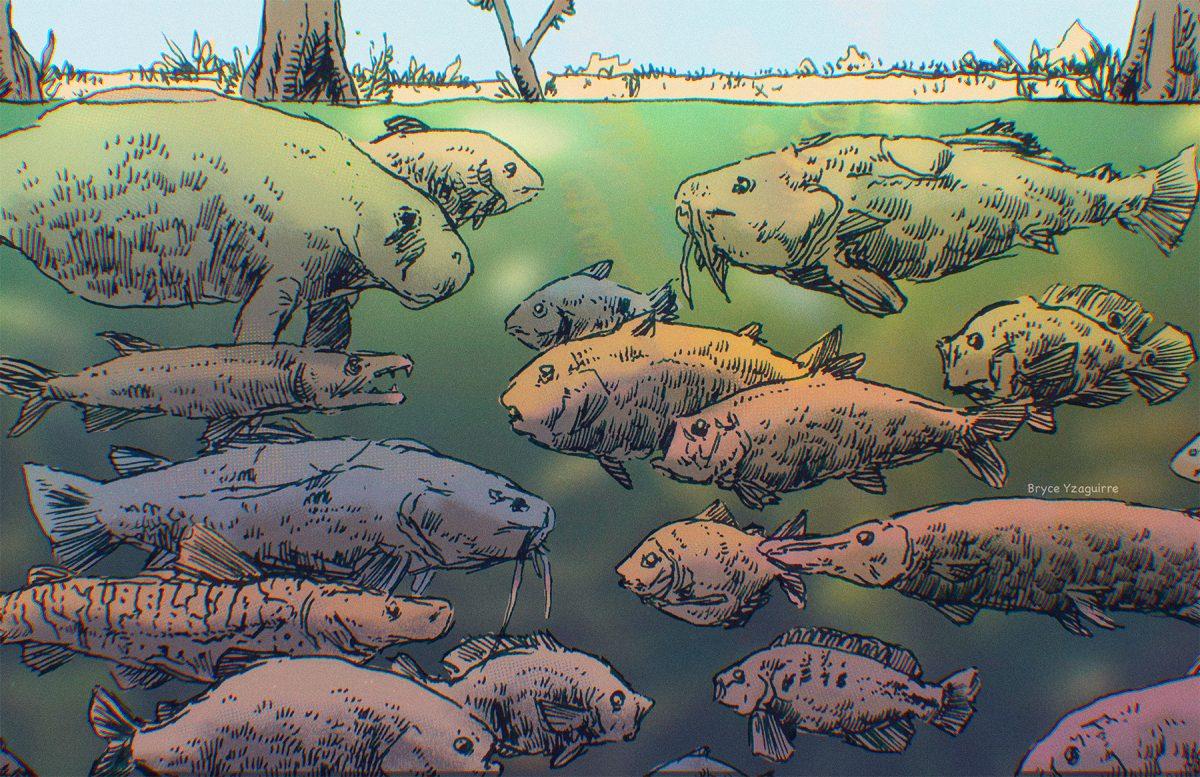

She remained in the steaming rainforest for seven more months. Every sample of fish from the nets was a surprise that shifted with the season, from giant, toothed fish to tropical cichlids with colored stripes.

Correa and her colleagues had run out of their supply of lentils, rice and oatmeal. She fished for every meal, pulling fish from the swollen lakeshore, but her team was running out of money to buy boat fuel and bleach to purify water.

They rationed their funds to purchase gas from a fueling station that also served as a monkey sanctuary. Nearly starving, Correa developed a deeper understanding of the fish subject to her research.

“Because then you understand the beautiful societies that are eating your fish and need your fish to survive and to generate income for themselves,” Correa said. “But then the other side of the coin is that it’s important to understand the fish is not just food, fish have a role in maintaining river health.”

Since her time as an undergraduate student in her native Colombia, Correa has applied her expertise in river systems to Mississippi, a place not unlike Amazonia. Now an assistant professor at Mississippi State University, Correa investigates the importance of river habitats to environmental conservation.

Many rivers in the U.S. are regulated with dams and levees, restricting the flow of water into a single channel. The Pascagoula River in southern Mississippi is the largest undammed river in the United States, with sprawling cypress swamps, oxbow lakes and pine ridges. Like the Amazon, the Pascagoula swells in an annual flooding season, transforming the surrounding floodplains into an aquatic ecosystem.

“That’s why I came to Mississippi, because Mississippi is a land of swamps and that’s basically what I’m specializing in,” Correa said. “…switch the trees and switch the fish and it is the same system.”

Correa is using the Pascagoula River as a reference point to identify the importance of these natural backwaters to fish species and what has been lost in other American river systems. Grant Peterson, a senior wildlife, fisheries and aquaculture major, went into the field with Correa in 2021.

Peterson said, based on the study’s preliminary findings, these temporary habitats play an important role in the reproduction of Mississippi fish species, providing young fish with protection from predation.

“I think this data and a bunch of other data that people are collecting on the river makes a strong case for how important it is to conserve it, and how important it is to keep these water bodies connected and not to alter them too much,” Peterson said.

Correa gestured to a map of the Amazon Basin on the wall of her office. She pointed out her hometown in Colombia, Popayán.

“It’s actually a very beautiful city because it’s colonial. It’s in the mountains, and it’s all like Spanish looking,” Correa said. “You know, one of those cities that has brick roads in downtown and very historical houses, all painted white with uniform balconies and flowers.”

Correa said she formed a childhood fascination with marine biology and scuba diving after watching television documentaries produced by Jacques Cousteau, an oceanographer who coinvented the first scuba gear. After a 1983 earthquake devastated Popayán, Correa’s family was forced to move to Cali, Columbia, where Correa began her undergraduate studies in marine biology at the University of Valle.

“I went to the biology professor, and it was hilarious because I had no experience, so I started helping him in the office, in the lab and I’d be like dusting the books and making photocopies,” Correa said, laughing.

Correa said growing up in Colombia has made her uniquely aware of the natural world and thus, more adaptable in the field.

“Growing up in Bolivar’s country gives you an awareness of the importance of biodiversity and a responsibility to study and protect biodiversity,” Correa said. “And I say a study because you can’t protect something that you don’t understand.”

This responsibility has drawn Correa to river systems across the world. Currently, she is working with the U.S. Agency for International Development in Cambodia to support the education of local fishermen on sustainable fishery management practices. Cambodia has little regulation on its fishing industry and its river systems are threatened by overfishing.

Correa pulled a waterproof bag from her office closet. Inside was a fish guide, a measuring board and a camera with a GPS unit that allows local fishermen to track what fish they catch, their size and where these fish are caught.

“The most commonly caught species are juveniles — so, baby fish. They’re eating baby fish that have not reproduced. So, it’s not sustainable over time,” Correa said.

Sitha Som is a doctoral student in the Department of Wildlife, Fisheries and Aquaculture under Correa. Also a Cambodian native, Som is a member of the Cambodian branch of the Wildlife Conservation Society. Som is leading continued research in Cambodia from MSU.

Som said continued research will map the floodplain of a threatened river in Cambodia, and use data gathered by local fishermen gauge the importance of natural backwaters to Cambodia’s fishing industry and turtle populations.

“The project is very successful under Dr. Correa’s analytical supervision,” Som said. “It’s very useful not only in terms of the scientific field, but it’s really important for Cambodia’s long-term fishery protection and for supporting the local community to be able to sustain and conserve their fishery all by themselves.”

Most recently, Correa’s focus has returned to the Amazon through funding from the European Biodiversity Partnership to answer big-picture questions related to the large-scale conservation of Amazonian wetland forests, and how these forests interact with river ecology.

“How is the connectivity on a much larger scale influencing fish diversity or where fish are located? So, the distribution of the species for the whole Amazon Basin,” Correa said. “Then the other thing we are doing is conservation planning. What areas should we protect, to protect the fish and the forest interaction?”

Correa was appointed by the United Nations Environment Programme to co-author a report on how to mitigate various environmental challenges, which is to be delivered during the 7th United Nations Environment Assembly in 2026. This report will seek input from local indigenous people, which has never been done before.

At MSU, Correa is consulting with various experts within the College of Forest Resources to bridge the gap between academic disciplines involved in environmental conservation. In the field, Correa lets undergraduate students take the lead.

“I just submitted my tenure packet, and I did a kind of tally on how many undergrad students are working on my projects, and it’s up to like 42 – and that’s the undergrads without counting the grad students,” Correa said. “I think it has been a really fun place to be – a place where I feel like I’m making a difference.”

Correa and her students used light traps to capture young fish.