Mississippi State University senior Madison Welzbacher has lived in Mississippi for 20 years, but she does not want to stay here.

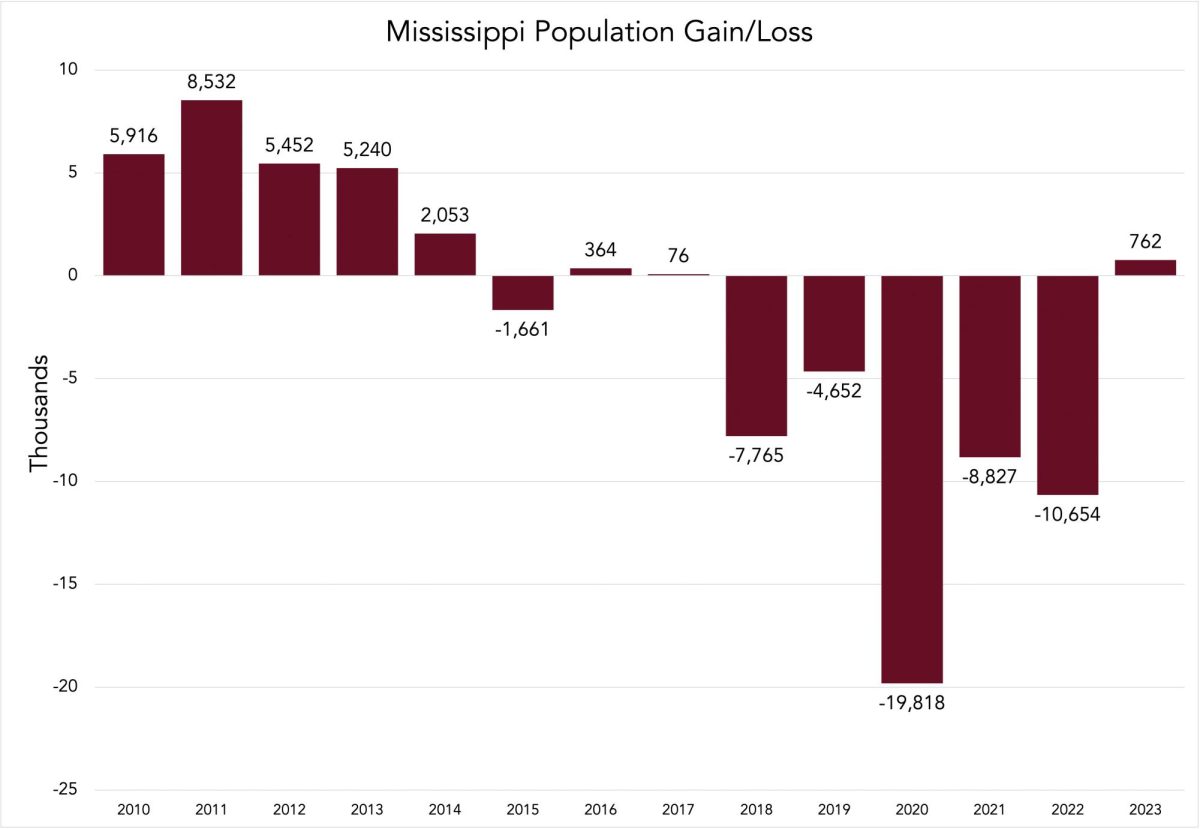

Welzbacher, along with many of her graduating peers, is planning to move away from the Magnolia State. Experts call this phenomenon of young professionals leaving the state and not coming back “Brain Drain.” It presents a problem for the development of the state because population numbers fall, and innovation slows. According to a report from the U.S. Congress Joint Economic Committee, Mississippi has the highest rate of net Brain Drain among southern states. Additionally, according to the U.S. Census Bureau, Mississippi is also the only southern state that has seen a population decline since 2010.

The report noted that the southern states are commonly among the states with the highest rates of Brain Drain, except for a few outliers with attractive metropolitan areas. Mississippi has no such attractive metropolitan area.

When asked if there was any other location or city in Mississippi she would want to move to, Welzbacher immediately said no. Jackson is the state’s capital and biggest city, but as Welzbacher agreed, poor infrastructure and high crime rates make Jackson less than appealing.

Welzbacher grew up in Corinth, a small town in northern Mississippi with a population of 14,000. She said the main draws for her to leave the state are, of course, a job, and also moving to a community that is more open-minded than the one she grew up in.

“It’s the Deep South culture I want to get away from,” Welzbacher said.

As for career options, Welzbacher pointed out that any type of creative career is going to be difficult to pursue in Mississippi.

The only thing that would keep Welzbacher in Mississippi, she said, was her family. But she said her family would probably want her to move away anyway.

“I’m very close with (my mom), and I would be sad to move so far away from her, but I don’t think that would scare me enough to want to stay, because I don’t think she’d want that either— for me to limit myself,” Welzbacher said.

A recent MSU graduate, Olivia Kwasny, was a special education major who was raised in Brandon, Mississippi, but has already left the state after graduation.

“I’ve always wanted to move out,” Kwasny said.

For an education major, Mississippi’s status as the lowest-paying state for teachers is a major drawback. Additionally, she mentioned there are not a lot of recreational activities for young professionals in the state.

“I feel like other states have more towns where you know a lot of young people are going because there’s a lot of fun things to do there,” Kwasny said.

Kwasny, agreeing with Welzbacher, mentioned that the only thing that would keep her in the state would be her family, such as if her parents started experiencing major health issues.

Hunter Rochester, a junior civil engineering major at MSU, also grew up in Mississippi but is set on leaving. Rochester pointed out Mississippi’s infamous issue with poor infrastructure.

“(Mississippi) lacks good infrastructure. Everyone knows that. And anyone who tries to come along and actually make changes to that is normally shot down,” Rochester said.

Rochester also said he feels the state of Mississippi in particular is resistant to change, an attribute that contributes to young professionals wanting to leave.

“I think Mississippi is so rooted in the familiar and conservatism as a whole, that you have the same kind of people being elected that just say the same things,” Rochester said.

MSU itself does research on the numbers of Brain Drain through the National Strategic Planning & Analysis Research Center, or nSPARC. Steven Grice, nSPARC’s interim executive director, explained how the state’s longitudinal data system (SLDS) allows them to align data across agencies and over time. This provides data on Brain Drain trends, such as the percentage of students with baccalaureate degrees who are employed in the workforce one year, three years and five years after graduation. According to nSPARC’s Life Tracks data aggregator, about 60% of graduated individuals were employed in the Mississippi workforce one year after graduation. Years three and five after graduation always saw a drop-off in participation.

Grice said being able to track the data is a step toward addressing the problem.

“If Brain Drain is a thing that people can measure and articulate, then there might be policy decisions or economic development strategies that can counteract that,” Grice said.

Daniel Morgan, senior coordinator at the MSU Career Center, advises seniors on their post-graduation plans. Morgan said he sees evidence of Brain Drain and said the main reason he sees students leaving is due to Mississippi’s lack of developed cities.

“A lot of what we hear is that certainly there are opportunities in more of an urban area. That really attracts a lot of students. Most students are looking for opportunities in larger populated areas,” Morgan said.

Morgan said the most common cities students from Mississippi settle in are Birmingham, Nashville, Atlanta and Austin. This is directly supported by the same report from the U.S. Congress Joint Economic Committee that says the top two states for Mississippi leavers to migrate to are Texas and Alabama.

Morgan also said that Mississippi has a few programs in place to address the issue of Brain Drain. One of these, the Mississippi Excellence in Teaching Program, is a joint initiative between the University of Mississippi and Mississippi State University to attract high-performing students and retain them to teach in the state. Additionally, the Mississippi House of Representatives passed a bill that would decrease state income tax for those who choose to enroll in the Mississippi workforce after graduation.

At the end of her interview, Welzbacher casually summed up why young professionals are choosing to leave Mississippi.

“We’ve got nothing here,” Welzbacher said.