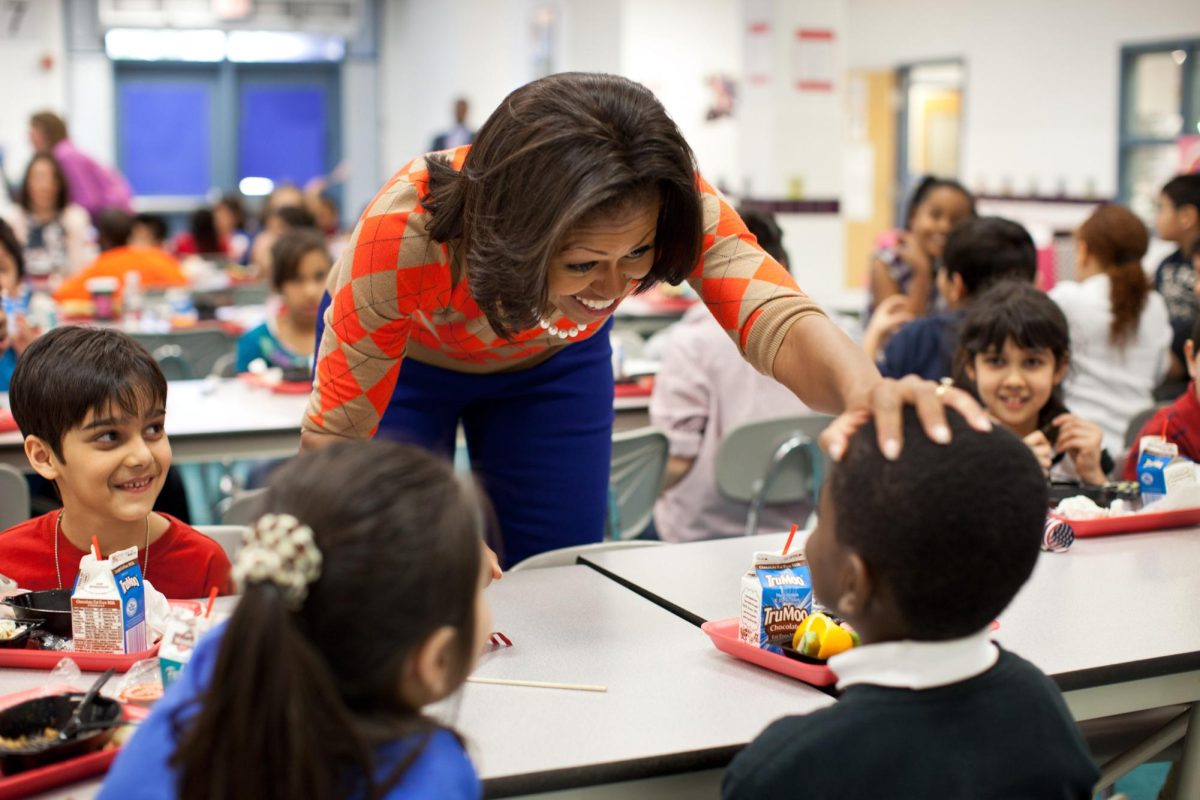

Turkey and ham club sandwich, hamburger or grilled chicken salad, potato wedges, steamed broccoli florets and fresh or chilled fruit, white, chocolate or strawberry milk — these are typical lunch options at Henderson Ward Stewart Elementary School. Their plates are plentiful with fruits and vegetables, a result of former First Lady Michelle Obama’s push to create healthy meals for children in schools.

The act was part of Obama’s “Let’s Move!” public health campaign that, according to the National Archives, “authorizes funding for federal school meal and child nutrition programs and increases access to healthy food for low-income children.”

According to the United States Department of Agriculture, the act has resulted in children across America eating 23% more fruit and 16% more vegetables at school. A “Health Affairs” study states the act has been “associated with a significant reduction in the risk of obesity for youth in poverty” and suggests participation be increased to reduce childhood obesity in the United States.

Scott Clements, state director for child nutrition programs with the Mississippi Department of Education, has been in this role for 14 years. As state director, he has seen the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act of 2010 implemented and how it has changed the way children eat at school. Clements feels that when the act was implemented, it was time to revise what was being served to children at school.

“It was a good way to align it to the Dietary Guidelines for Americans,” Clements said. “So the great things that came out of it was an increase in the numbers of fruits and vegetables that were consumed by children. It brought us increased emphasis on fat and sodium that was being served in those meals.”

Clements has seen the financial and logistical challenges associated with the act.

“As the foods become more and more specific to schools, you have less manufacturers competing for that business,” Clements said. “…And during COVID, of course, that was exacerbated because you had a lack of products on the market, so we were scrambling to get those products into our system. And when you accompany that, the cost goes up, so it’s harder for schools to get the items on the tray and make it cost-effective on a limited amount of reimbursement.”

Ginny Hill has been a registered dietician for 15 years and has been the child nutrition director in the Starkville Oktibbeha School District for 10 years. She has seen the challenges in the nutritional side of the act.

“One of the regulations was every grain that we serve needed to be 100% whole grain. So we are in a southern state in Mississippi, and whole grain foods are not part of our meals, just as a Southern culture,” Hill said. “So that was a huge point that we had to adapt to to increase the consumption of whole grains and prepare those in a way that they were received well.”

One example of Southern food culture food is a biscuit. Hill said a whole-grain version of biscuits is not typically consumed in the South, so it was not a great product and was not received as well by students. She said schools are now on a grain waiver that allows them to operate on 80% of whole grains instead of 100%. This adjustment, as well as several others, was made due to poor receptiveness from students or the inability of the food industry to meet the legislation requirements.

Hill said that while the guidelines for the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act are in place, it is important to meet students in the middle to serve them food they will want to eat.

“If we serve a healthy meal that a student doesn’t eat, all we’re producing is a healthy trash can,” Hill said. “And that gets us nowhere.”

Hill recognizes that some children may not be eating as healthy when they are at home compared to at school, which contributes to poor reception from children.

“While it’s important that we have low-sodium meals and show students what examples of healthy meals are, our students, for the most part, are not consuming low-sodium meals at home. Their parents are not preparing them,” Hill said. “So when they come to eat with us and we’ve prepared something low sodium, they receive that as bland or not having any flavor. So we’ve had to do a lot of adjustments to make our food have more flavor to meet them when they’re not used to eating low-sodium food.”

Qula Madkin has been a registered dietician for 23 years and an extension instructor at Mississippi State University for four years. She has a personal connection to Michelle Obama’s health initiatives for children through her daughter Aniya. In 2016, Aniya was chosen to represent Mississippi in the Kids’ State Dinner Cookbook as part of Michelle Obama’s Healthy Lunchtime Challenge in the “Let’s Move!” campaign. With her healthier take on a Southern dish called “Kickin’ Cauliflower Shrimp and Grits,” Aniya was able to meet the First Lady. After experiencing the effect that the program had on her daughter and other children firsthand, Madkin saw the positivity in what Michelle Obama was doing for children across the country.

“She just really had the sense of encouraging nutrition and wellness,” Madkin said.

Clements, Hill and Madkin all feel that the former First Lady left a positive legacy and lasting impact in Mississippi with the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act. Clements feels there have been many positive changes as a result of the act.

“I think it has improved the quality of school meals,” Clements said. “I think it’s improved the environment and, you know, the water and the Smart Snacks inside the school.”

Hill feels the legacy of the act remains positive.

“It has changed how school meals are prepared, and it has changed the meals and the menus that we serve,” Hill said. “…we talk about what it reflects and how we’re showing students what healthy meals look like and giving them that exposure.”

Madkin thinks that changing the way people eat can be very personal but says Michelle Obama did it positively and compassionately.

“I think the legacy is positive change takes time,” Madkin said. “…you can tell from what they did and all the things that are even left over, even looking in the archives from some of the “Let’s Move!” or the Healthy Lunchtime Challenge, it’s extremely positive, and they were in full support of children and families really, when you got down to the nuts and bolts of it.”

Madkin is an advocate for encouraging children to eat healthier and encourages the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act. However, she believes it is important for children to have something to eat regardless of whether it is considered to be healthy or not.

“I want them to have fresh food — fruits and vegetables, whole grains, lean protein, healthy fats. But when it comes down to it, I just want parents to have the opportunity to be able to feed their children,” Madkin said. “And sometimes that’s going to be what it’s going to be whether I think it’s healthy or whether you think it’s healthy or anyone thinks it’s healthy or not. I just want children having food period… there shouldn’t be shame around families, moms and dads… grandparents, guardians, foster parents, whatever it may be, in feeding their children what they have to feed them.”