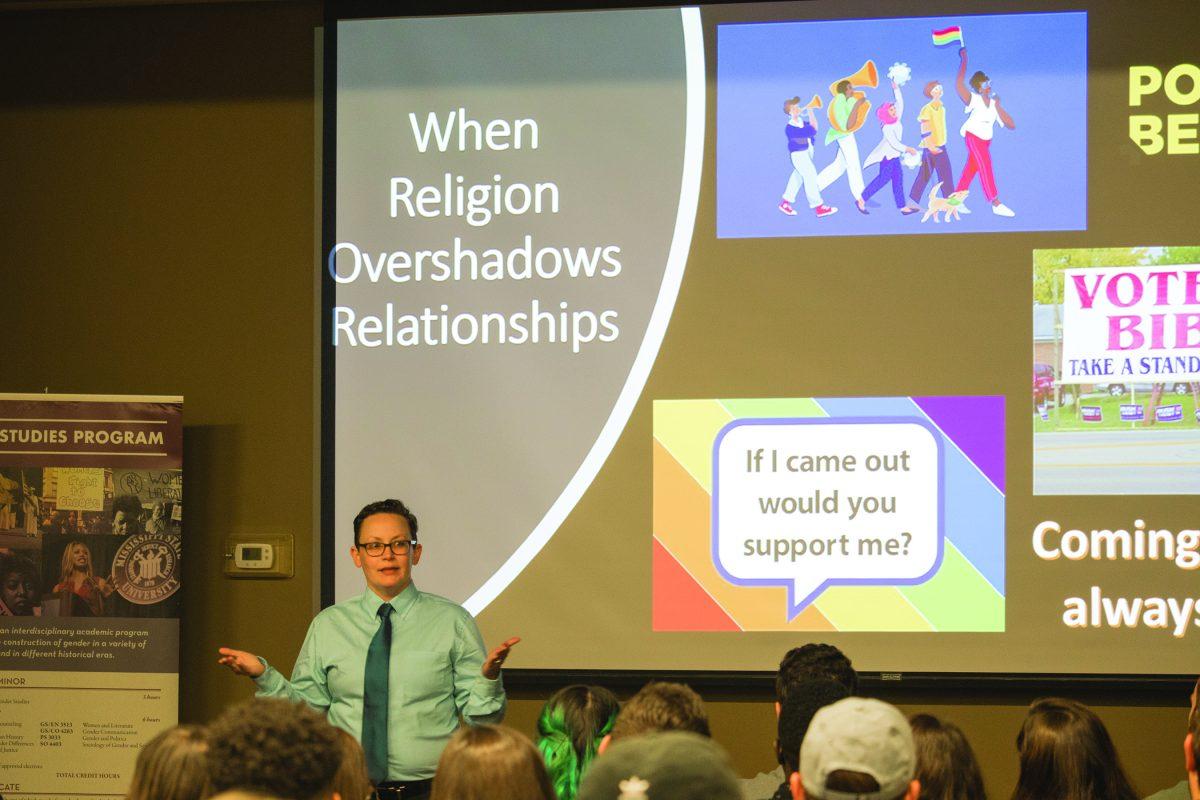

Mississippi State University’s Gender Studies program hosted a book lecture by Baker Rogers, Georgia Southern assistant professor of Sociology, Thursday in the Griffis Hall forum room.

Rogers is the author of “Conditionally Accepted: Christians’ Perspectives on Sexuality and Gay and Lesbian Civil Rights,” which is set to be published in December of this year by Rutgers University Press. The book analyzes the beliefs Christians in Mississippi have about homosexuality and gay and lesbian rights, as well as the influence a gay or lesbian loved one has on these beliefs.

The talk, entitled “Conditionally Accepted: The Influence of Coming Out to Mississippi Christians on Lesbians and Gay Equality,” explored the numerous effects religion can have on beliefs regarding gay rights.

The talk opened with a welcome from the Director of Gender Studies at MSU, Kimberly Kelly.

The “Conditionally Accepted” lecture was scheduled in celebration of National Coming Out Day, Kelly said, which took place during Fall Break on Oct. 11. This year marks the 31st anniversary of National Coming Out Day.

In the days leading up to the lecture, those involved in the Gender Studies program were eager to have Rogers, an MSU alumna, back to Starkville.

“The Gender Studies Program is very pleased to host Dr. Rogers for our annual National Coming Out Day event, not only because of her important work on the connections between religion and LGBTQ+ equality, but also because she is an MSU alum,” Kelly said. “We are delighted to welcome her back to campus.”

Rogers graduated from MSU in 2015 with a PhD in Sociology and worked as the Gender Studies Program Assistant from 2013-2015.

Rogers opened the talk with a simple question: What is coming out? Her response was that coming out is a career and lifelong process.

“I came out for the first time in 2003, and I’m coming out again tonight to those of you who haven’t met me,” Rogers said. “You come out every time you meet a new person or go to a new place. You’re straight until proven otherwise.”

Rogers identifies as a genderqueer lesbian. Despite its normalization over recent years, Rogers believes coming out still serves as a function of oppression. Those who enjoy positions of privilege in society, such as straight or white people, are not asked to come out, Rogers said.

With every new set of students she teaches, Rogers questions coming out, especially as a professor in a southern state.

Following this discussion, Rogers leapt into explaining her research. The interviewees included 28 women and 12 men, four of whom were black and 36 of whom were white. This group was further split into 10 Evangelical Protestants, 19 Mainline Protestants and 11 Catholics. The interviews were conducted face-to-face and over the phone.

Rogers offered a number of stories about her time spent interviewing Mississippi Christians. One such story took place over a phone interview, when an interviewee prefaced even a simple greeting with a question: “Are you gay?”

When Rogers responded yes, the woman replied, “Well, I guess I can talk to you, as long as you can be objective.”

Out of the interview pool, 18 people said they had a gay family member, 31 had a gay or lesbian friend and six had no gay or lesbian friends or family members.

This was an interesting statement in itself, Rogers explained, because the sole reason she had contacted the selected group was because of their affirmative response in a preliminary survey.

From the group of interviewees, only six people responded positively to their gay friends and family members, the smallest group represented in Rogers’ study.

Rogers’ results divided participants into four categories: A Case for Coming Out, Allies and Friends, Love the Sinner, Hate the Sin and Homosexuality is an Abomination. The ranking is from most supportive of gay friends and family to completely against them.

A majority of interviewees fell into the Allies and Friends segment, but these people stated that having a gay friend or family member had no effect on their beliefs.

Out of the three religious groups interviewed, Rogers found Mainline Protestants had the highest response rate to supporting a homosexual friend upon coming out, while Evangelical Protestants had no record of this response.

Another of Rogers’ stories featured a woman who said she had continued with her religion in spite of her gay son. When Rogers asked if this had affected their relationship, the mother responded that it had not.

Encouraged, Rogers then asked if she and her son were still close. To this, the woman answered, “No, not anymore.”

Despite 31 years of National Coming Out Day, coming out has not been the end-all, fix-all of homophobia, Rogers said.

“All the students in the room are going to write the book on what we need to end homophobia because I definitely don’t know what it is,” Rogers said.

The event was followed by a question-and-answer panel. During this time, Rogers admitted she never actually came out to her parents, and instead continued to bring home partners until they got the message.

Nathan Yos, a junior Biological Sciences major, attended the talk because Rogers’ research reminded him of the environment in which he grew up, and he wanted to see if her research aligned with his personal experiences.

“I thought the book talk was intriguing as it gave personal accounts of what some Christians believe about their LGBT friends/family and helps explore why they believe the certain things they do,” Yos said. “Even with a clear lack of a sizable sample size to draw any sort of conclusion, it points out how much this area needs to be explored in order to foster understanding and tolerance between people of the Christian and LGBT communities.”

Rogers plans to publish another book with the information she received from follow-up interviews featuring the people she originally interviewed six years ago. She currently has another book, “Becoming Me(n): Trans Men in the South,” in the works.

‘Conditionally Accepted’ talk explores Mississippi Christians’ beliefs on gay rights

Adam Sullivan | The Reflector

Baker Rogers, a 2015 MSU PhD graduate and assistant profressor at Georgia Southern, presented Thursday on her research on coming out in Mississippi.

0

More to Discover