“What are you going to do with that degree? You are never going to make any money. Do you really like to read? Are you sure? I bet your schedule is so easy. Did I mention you are not going to make any money?”

I have heard some variation of these little quips and questions ever since I decided to major in English the spring semester of my senior year of high school.

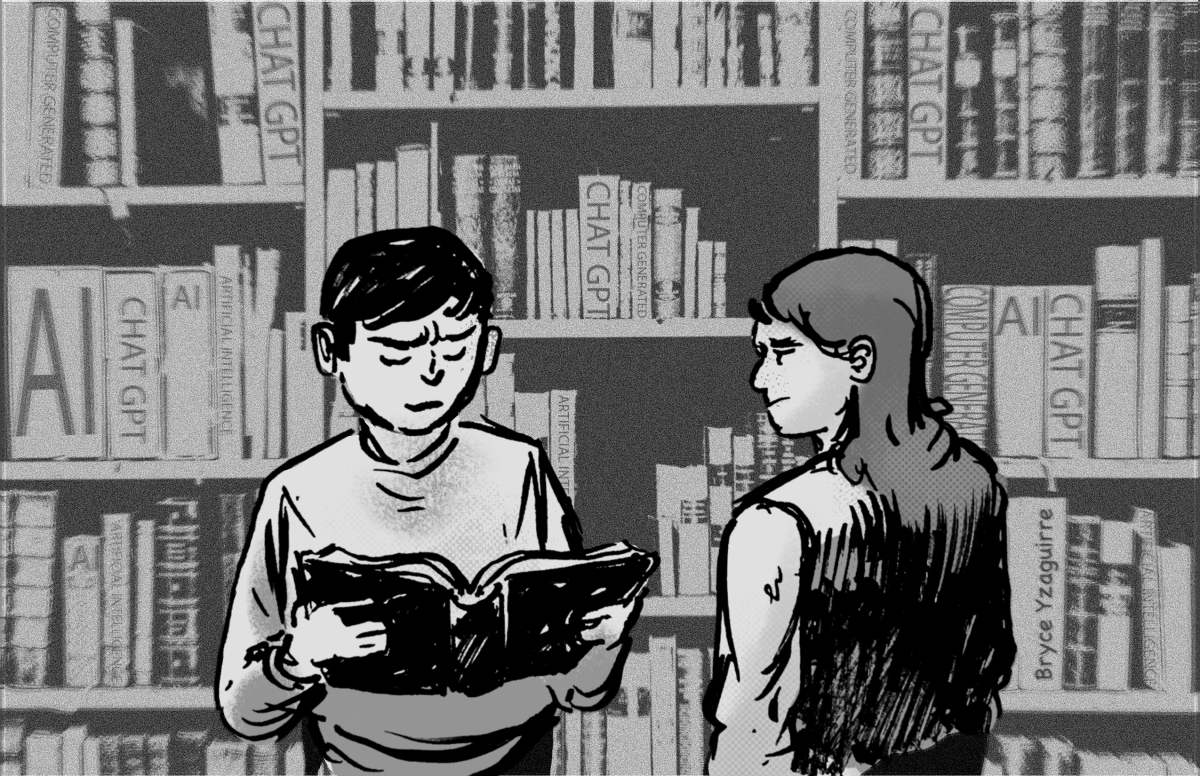

While I have watched my English-teacher mother impact so many lives with good books and classroom conversations, I must admit that sometimes these comments make me question my life choices. I cannot say the loss of humanities programs across the nation and the rise of ChatGPT have not exacerbated my doubts either.

However, I still believe that the reading, writing and thinking that occurs in the English classroom equip students to grow as scholars and people. I fear the day when people stop reading and writing for themselves — when universities lose the few English majors left who still declare the importance of works written by humans about humans.

For me, literature classes allow people to learn from the past, communicate in the present and change the future. When I read about a character, I have the opportunity to understand that character’s story and practice empathy. I can learn to appreciate others’ stories, as well as develop my own story by reading.

As for writing, I do not necessarily believe that everyone needs to know how to produce a ten-page research paper for their careers, but I do think the same people who gripe about the assignment will need to communicate with other people unlike themselves, recognize propaganda and establish a sense of self to be productive members of society. All these skills directly stem from the writing process.

I spoke with Eric Vivier, associate professor of English in the Shackouls Honors College, about the dwindling support for humanities programs across the nation.

I asked him a question that has been haunting me recently: What do you think will happen if we continue to see humanities programs die, and what does this mean for our students, our nation and our world?

After a long, pensive pause, Vivier answered.

“I think there is a fairly direct correlation between engagement in the humanities and commitment to democratic principles,” Vivier said.

Vivier also explained, “The world becomes a flatter, duller place that only seems to recognize or accept certain values and certain types of value. Numbers become everything. The humanities allow us to recognize that there are forms of value that cannot be quantified.”

We have an obligation to each other to think deeply and critically — to engage with media beyond the five-second clips on our phones and to communicate with people beyond shallow likes for the sake of our relationships and our nation.

I worry that my peers and future students will lose the ability to make judgements about value, power, inequality, truth, gender, race and class if we continue to disrespect the humanities and discourage high-achieving students from majoring in fields like English that force people to grapple with such topics.

Vivier described the English classroom as an “imaginative playground where sometimes real world problems can be made clearer through fiction.”

Well, we are destroying that playground in the name of progress and ignoring the real world problems altogether.

I think the rise of ChatGPT does not raise the question “Is English education still valuable?” Instead, it asks, “Will we realize the value before it is too late?” ChatGPT allows people to produce writing without engaging in the process. Students who use AI to write their English assignments entirely rather than as a drafting tool do not develop those analysis skills. They forfeit their voices, and they doom us to a future without freethinkers.

I ultimately fear ChatGPT not because the technology can write a faster or better paper than me, but because its convenience threatens the development of critical thinking in the first place.

Vivier explained his similar fear. “I worry about the day a student submits a paper from ChatGPT, and the student receives feedback from ChatGPT — cutting people out of it,” Vivier said.

Despite these fears, I recognize that this technology saves time and money. Like a calculator, ChatGPT can be used as a tool, and while I am not optimistic about its impact on the English classroom and the development of young minds, I do not think all hope is lost.

Gregory Francom, a professor in the Instructional Systems and Workforce Development Department, emphasized the impacts ChatGPT will have on education.

“ChatGPT as a generative AI tool is here to stay. It is not like another one of those fads in education that comes and goes. It’s going to be a part of the way we work,” Francom said.

Francom even discussed a survey he did that revealed that 70% of his current students admitted to already using AI materials, which sparked a conversation about the importance of instructors shifting their strategies in the classroom.

“You need to have a conversation with your students. What are unethical vs. ethical uses of ChatGPT? Become a partner with them,” Francom said.

Essentially, Francom, Vivier, my mom and countless other educators are having to change the way they teach to discourage unethical use of technology.

Who has the skill to communicate with students about tough moral issues that change society, to restructure the education model to help students navigate a new tool but not at the expense of their own critical-thinking?

The English major.

The disrespected and disillusioned English instructors and students must listen to their families and colleagues and nation tell them that ChatGPT has made their skills obsolete, all when they alone know that good books and good thoughts must be preserved.

Categories:

AI not a suitable replacement for real-life humans

About the Contributor

Rowan Feasel, Staff Writer

Rowan Feasel is a junior English major. Rowan is currently a staff writer for The Reflector.

0

More to Discover