“I was born and raised in Starkville, right over the hill,” native of the Needmore community, Harvest Collier, said. “In fact, on Spring Street, I sit on the front porch of my mom’s house. I can see the rim of the football stadium and on Saturday evenings I recall hearing the crowd – and the cowbells – but I knew nothing about them.”

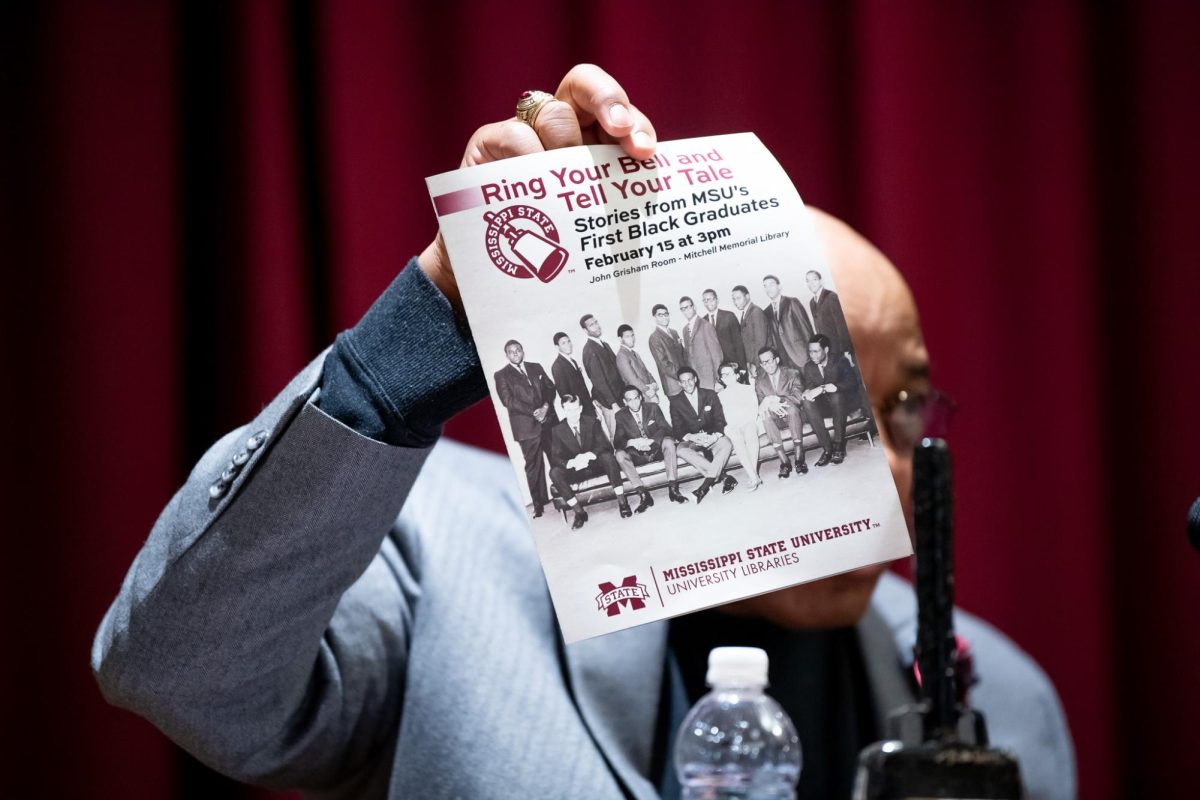

Collier, along with Colonel Robert Barnes, Doug Milton, Linda Milton and Vernon White, made up “Ring Your Bell and Tell Your Tale: Stories from MSU’s First Black Graduates,” a panel discussion about the university’s first Black student experiences Friday afternoon.

“The environment here was totally strange to me, despite the fact that I suppose you could climb to the top of the football stadium and look west, you can see my mom’s house. But I’d never come to campus – I had no sense of what it was like, growing up and living in a totally segregated environment,” Collier said, who entered MSU in 1968. “So, you can imagine the cultural change that I had to figure out in arriving here.”

The panel was a culmination of the project “Ring Your Bell and Tell Your Tale: The History of Black Students at Mississippi State University, 1965 to 1975,” which aimed to capture the experiences of Black students through interviews, the review of primary documents and the analysis of The Reflector articles produced following MSU’s integration in 1965. The yearlong effort between alumni and university faculty will produce a scholarly book, documentaries, websites and a soundtrack.

Colonel Barnes, a panelist and an alumnus who worked on the project, sat alongside his former classmates as he recalled his first semester to the audience filling the library’s John Grisham room.

“When we sat down in the classroom, there was never a white person sat to left or to the right. If the classroom was full – some of these classrooms were fairly small – someone would move and stand up. Even in one of the bigger classrooms, in one of these big auditoriums, no one that didn’t look like you sat beside you,” Barnes said. “Maybe as I got to be a senior there were only one or two black people in a class – most classes there was only one black person in that class. So, as soon as class was over with I went to see if I can have a conversation with people. So, we found our community.”

Barnes said Black students began to regularly meet outside the YMCA Building, the group growing through word of mouth. This community became the foundation for Afro-American Plus, MSU’s first Black student organization which was founded in 1968.

Doug Milton, a native of Laurel, Mississippi, said his parents were very active in the Civil Rights Movement in Jones County, the county with the highest per-capita population of Ku Klux Klansmen. He graduated from R.H. Watkins High School three months before the school system integrated and came to MSU in 1970, where he met his wife, Linda Milton. Milton said 95% of campus was politically active at that time.

“I came here and what I realized when I got here, is people like Robert and Harvest – they were so receptive, I think, had a whole new family when I got here. When I got here there were 36 back people total. But you know, it was like a small family that told you everything you needed to know. You know, they looked out for you. And if you were sat down at that picnic table when the chime went out from the chapel, they encouraged you to go to class,” Milton said, who eventually graduated from MSU in 1979 with degrees in political science and history.

Collier said the campus experience outside of Afro-American Plus forced him to seek out opportunities and brought him confidence in his ability to learn.

“I think it was the usual challenges that students have with senses of belonging; a lot of isolation, even if it’s day to day going to class, you took one of those classes that require a person to work with you like a laboratory, for example, that you needed the lab partner. I recall it being really difficult to have people volunteer to partner up with me in the lab. But what happened was: you gained some great insight about resilience and doing things that needed to be done and learning not to have simple things be barriers for you,” Collier said, who graduated from MSU in 1977 with a doctorate in chemistry.

During the panel’s reception, Barnes reflected on a goal in Afro-American Plus’ founding constitution: “To acquire self-identification.”

“We would not accept being second-class citizens. Our talents, not just physical attributes, but our mental ability, our social ability – we’re just as good as everybody else. Not better, but definitely not worse,” Barnes said. “So, self-identification means that we could be our authentic self and we didn’t have to rely on others, we could rely on ourselves.”

The project created a digital archive of more than 600 articles, advertisements and images from The Reflector to collect stories that seeks to inform research and motivate MSU students today.

“The whole idea of research with The Reflector was to see those worldly events translate to state events, translate into campus events which translated to our lives and how we reacted to that. For everything that happened, if Black students would do something or say something, there would be a letter to the editor, ‘Oh, why are they doing this?’ But on the other hand, there will always be a lot of from the Black students to The Reflector to say, ‘Well, here’s the way we see it,’” Barnes said, who graduated from MSU in 1972 with a degree in sociology and anthropology.

“…but if we don’t tell their real story, those stories won’t get told. I think it’s very important that we tell their story – firsthand information – not just looking back, but firsthand accounts of their lives and how they made a difference,” Barnes said.