Amidst the ongoing COVID-19 crisis, we have recently developed the most powerful weapon yet in the battle against the virus. American pharmaceutical companies Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna have developed vaccines in a time unprecedented in human history, and for the first time in almost a year, we see a light at the end of the tunnel.

These vaccines, though still new, are reporting a 95% effectiveness rating in giving immunity to the virus. Armed with our new weapon and the coming of the warmer months, there is reason for optimism that we may soon get the pandemic under control. However, since research and development of the vaccines have been completed, our goals have seemed to shift away from saving lives, the primary objective of our COVID-19 protocols.

Once an effective vaccine is developed, managing the pandemic ceases to be a scientific or even a medical issue but rather becomes a logistical issue, a production issue. Mass-scale production does not happen instantly.

According to Lauran Neergaard with the Associated Press, “(Vaccines) must be made under strict rules that require specially inspected facilities and frequent testing of each step, a time-consuming necessity to be confident in the quality of each batch.”

These COVID-19 vaccines are especially volatile, requiring specific temperature control for transportation and storage.

Even with ample time to produce, Noah Higgins-Dunn with CNBC reports the U.S. is only on its way to receiving about 100 million shots of the Moderna vaccine by March and another 100 million by June, not enough to immunize the entire country. The present demand for COVID-19 vaccines far outpaces the supply. Until our production capacity can balance the scale, we are forced to triage our resources, and we should distribute in the interest of saving as many lives as possible.

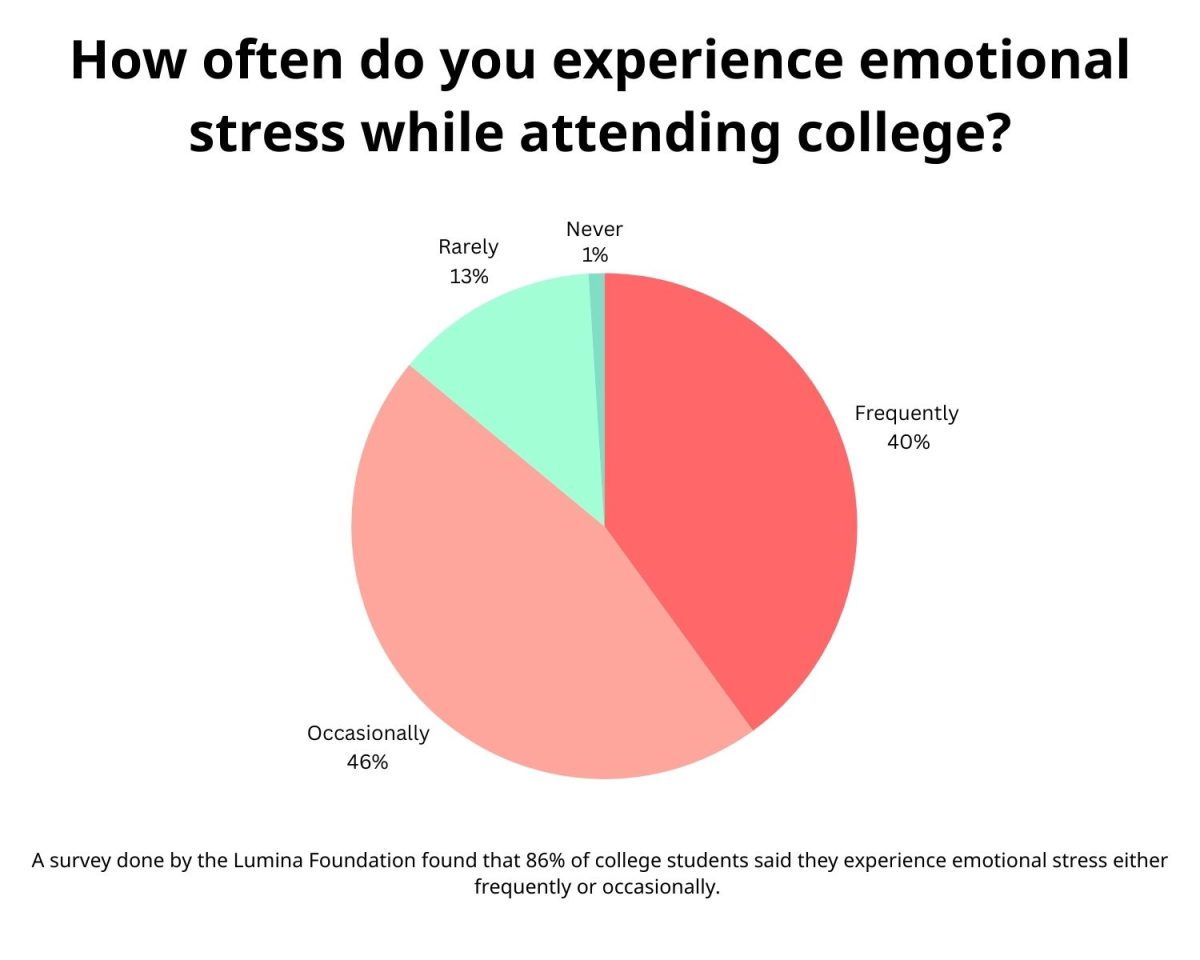

College-aged students are at some of the lowest risk across the entire population of the U.S. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, people ages 18-29 only represent 0.5% of total COVID-19 related fatalities.

This disease is not a killer for younger people, and as a result, the vaccines reserved for students should instead be reserved for those who are likely to die as a result of contraction such as the elderly or the immunocompromised. It would make sense to inoculate students of our age group if our primary motivator was to limit case numbers as opposed to deaths, as people ages 18-29 represent the highest case number of all groups with 22.6% of the share according to CDC statistics.

However, the overwhelming majority of people our age recover with no lingering effects outside of a natural immunity which protects the infected for a minimum of six months.

Even though people who are asymptomatically infected develop an immunity to the virus, millions of Americans could be conducting their day-to-day lives completely unaware they themselves are immune to a virus they never knew they had. These Americans could just as easily go get a dose of the precious COVID-19 vaccines which are currently in such short supply to inoculate them for a disease for which they are already immune. Several of these Americans could be college students and people our ages, the group with the highest number of asymptomatic spreaders.

Minimizing the number of poorly allocated vaccines is essential in controlling the spread of the virus, and the most efficient way to minimize waste is to require an antibody test of the patient prior to injection. Personal antibodies are a more effective preventative measure than the COVID-19 vaccines by every metric, and testing for them prior to inoculation will help us save more doses of vaccines for those who do need it and will, in turn, save more lives.

Even beyond conducting an antibody test, giving mass amounts of vaccines to university students is not an optimization of resources, even when the primary goal is to limit the spread of new cases because universities are not even close to the most virulent vector of transmission.

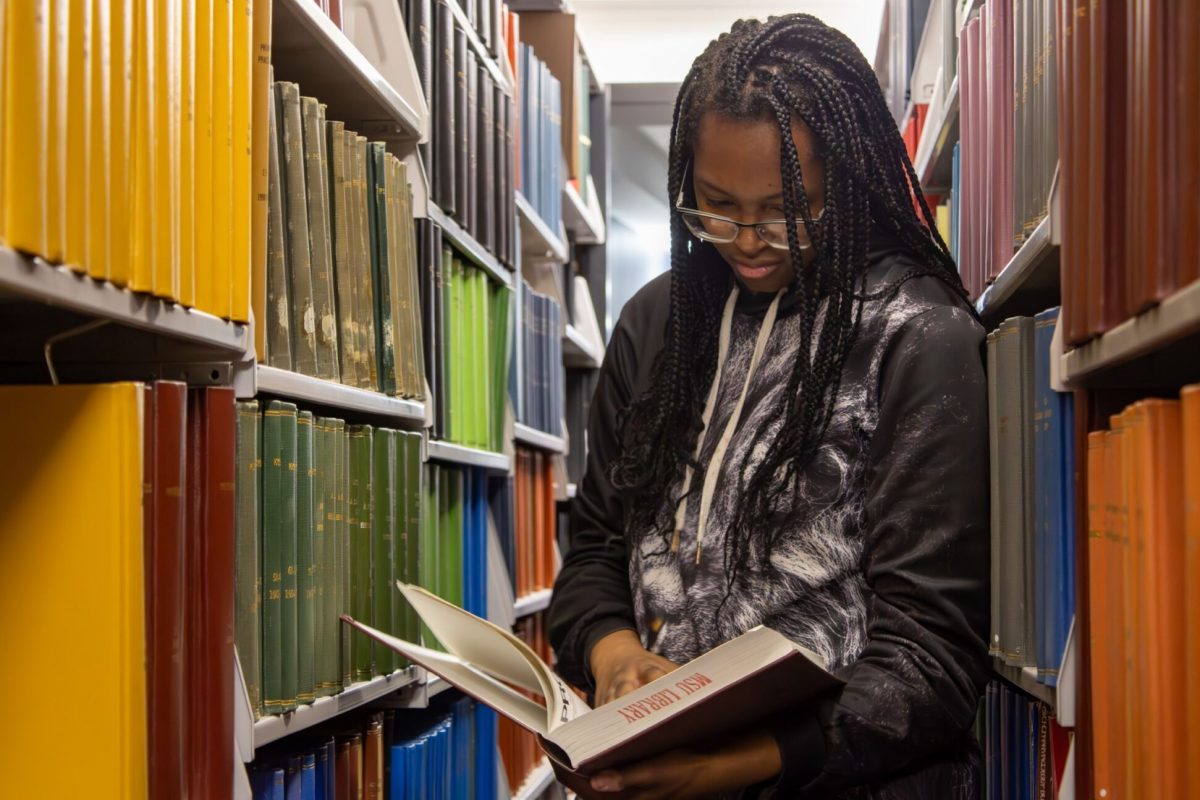

According to Dr. Adjoa Smalls-Mantey of ABC News, 70% of the new COVID-19 cases arise from small gatherings and households, and it is not difficult to understand why. These informal gatherings usually consist of family and friends spending large amounts of time together without COVID-19 guidelines in place. Expecting people to follow these guidelines while in their own homes is unreasonable. Masking, social distancing and general protective measures are disregarded. Therefore, the transmission rate during small informal gatherings is much higher, even in instances where the number of people may be lower than a university like Mississippi State University.

MSU’s diligent adherence to CDC guidelines through their Cowbell Well program as well as having the proper infrastructure in place to address the pandemic as best as the university can has drastically decreased campus transmission rates. Vaccinations would no doubt bring university transmission rates down even further, but the introduction of vaccines would not have as much of an impact on the overall trajectory of the pandemic as if they would have been introduced into a more at-risk population. And of course, logistically-minded distribution of the treasured few doses of the vaccines which we do have will inevitably save more lives than wide-scale vaccination at random.