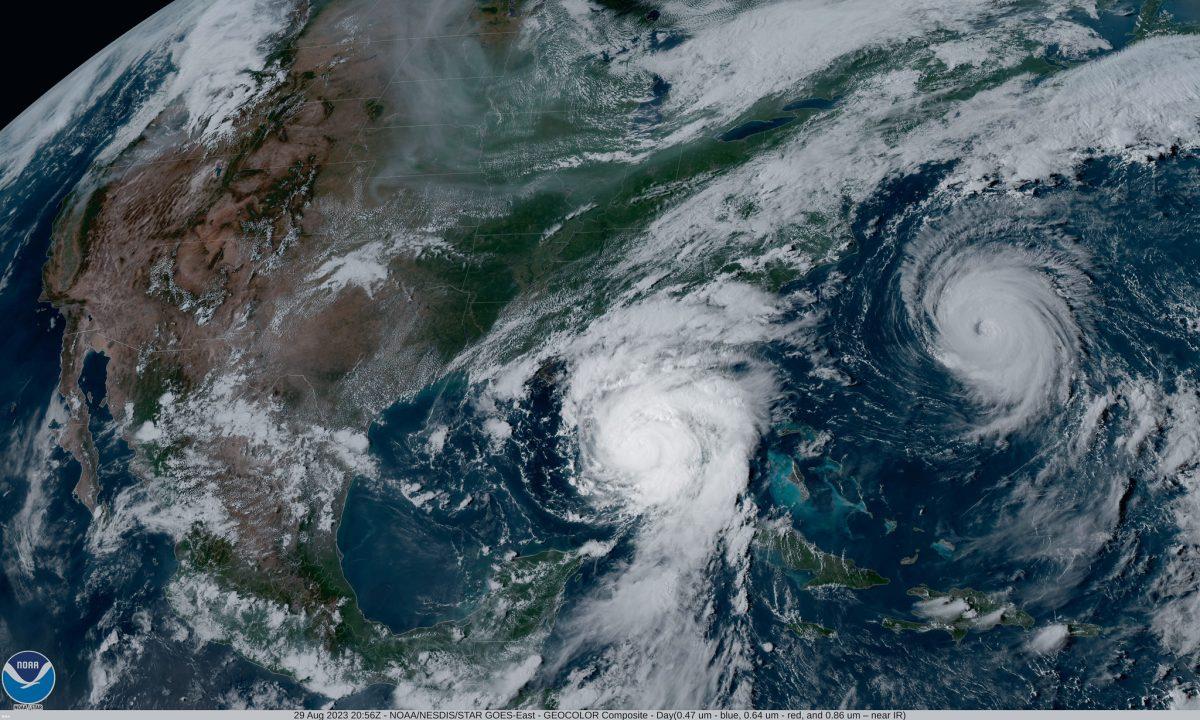

The National Centers for Environmental Information reports that tropical cyclones are the costliest weather and climate disaster annually in the U.S. Between 1980 and 2022, U.S. tropical cyclones accounted for $1.3 trillion in damage. In 2022 alone, tropical cyclones cost the U.S. an estimated $120 billion in damage.

A 2021 ScienceBrief review of more than 90 scientific articles reported that the intensity and rate of intensification for tropical cyclones have increased slightly since the 1980s, and globally, the average frequency of tropical cyclones is expected to decrease by about 10%, while the average intensity of these storms is expected to increase by 5% if the earth warms by two degrees Celsius.

Scientists across the globe are still identifying how a warming earth will impact tropical cyclones. Here in Mississippi, researchers at Mississippi State University are using climate models in three different research projects to investigate the effects of climate change on tropical cyclones.

Climate Models: A Climate Scientist’s Best Friend

Climate models produce a virtual simulation of meteorological and climatological events on a gridded map of a geographic area. The first climate models had very large grid boxes making for less accurate projections. As computing power has improved, the size of models’ grid boxes is shrinking, providing better resolution and improved accuracy.

Boniface Fosu, an MSU assistant professor in meteorology and climatology, said though the resolution of climate models has improved over time, climate models still have limitations. A typical climate model has 100-by-100-kilometer grid boxes. While the model can account for tropical cyclones (which have an average diameter of 600 kilometers), it cannot simulate the eye of these storms because a typical tropical cyclone eye has a diameter of only 25 kilometers. Simulating the eye of the storm is important because scientists determine the strength of a storm (whether it’s a category one, category two etc.) based on analysis of the storm’s eye.

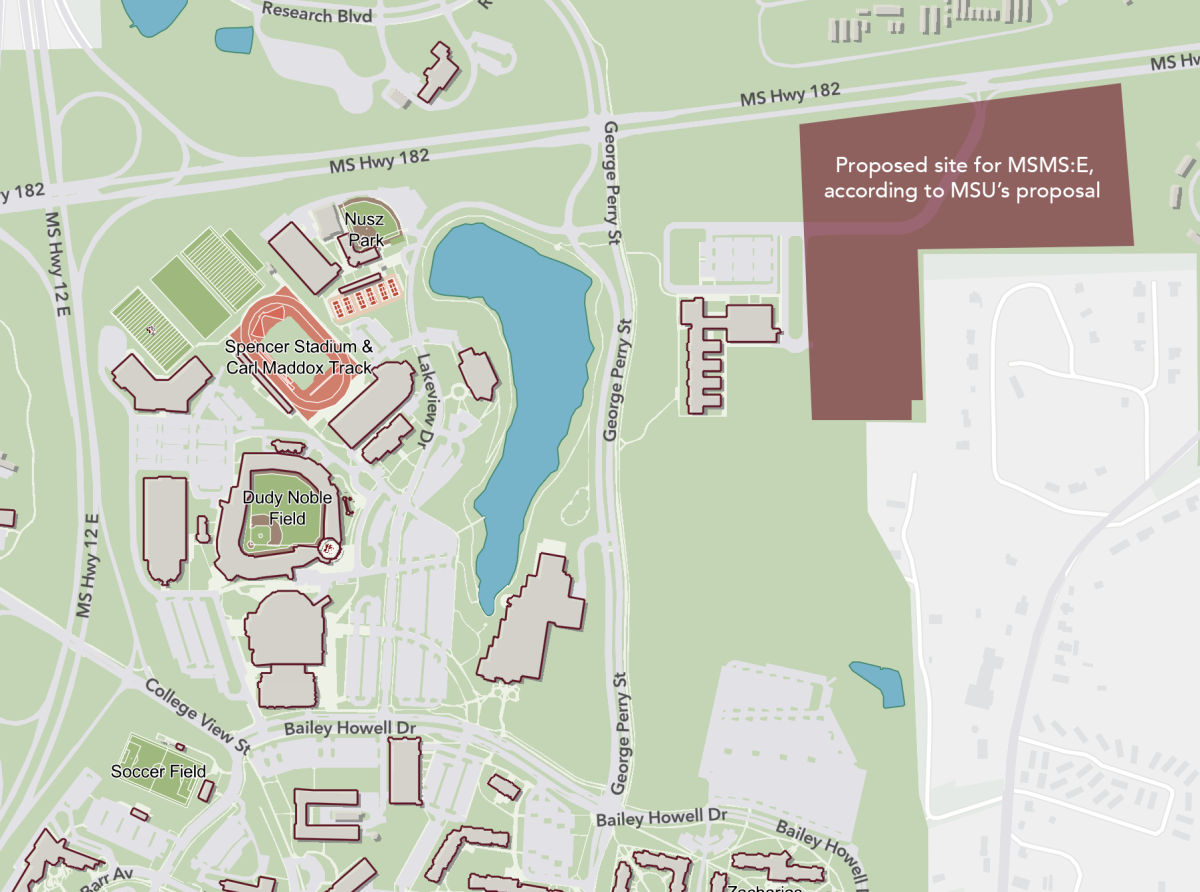

In climate modeling research projects, MSU researchers will downscale the climate models so that they provide finer resolution, allowing the model to simulate smaller processes. This involves taking the model down to a regional scale that will focus on the Gulf of Mexico.

Climate Change, Tropical Cyclones and Petrochemical Spills

MSU researchers are using climate models in a $1.5 million project funded by the National Academy of Sciences (NAS) that focuses on how overburdened communities near petrochemical storage facilities will be affected by future tropical cyclones. The project is a collaboration between MSU, Columbia University and Rice University.

The Environmental Protection Agency defines overburdened communities as “minority, low-income, tribal, or indigenous populations or geographic locations in the United States that potentially experience disproportionate environmental harms and risks.” Researchers on the NAS project are studying overburdened communities around Baton Rouge, Louisiana and Houston.

Tropical cyclones in the Atlantic Basin have a history of wreaking havoc on coastal communities and ecosystems by causing petrochemical spills. In 2017, Hurricane Harvey damaged storage tanks on the Texas coast, releasing hundreds of thousands of gallons of oil into the surrounding area. During Hurricane Katrina, millions of gallons of oil were spilled into the ecosystems and communities of coastal Louisiana.

Climate scientist Fosu is leading the project. Fosu said the team will take inventory of the petrochemical storage tanks in the Baton Rouge and Houston areas and will evaluate the structure of the tanks. Using this data, they will investigate how well the tanks will hold up during a future cyclone.

The research team is using a Columbia University model that simulates the impacts of storm surge. MSU researchers will be incorporating a precipitation component in the model to simulate impacts caused by heavy rains and flooding, something that has never been done before.

Yen-Heng Lin is an MSU researcher working on the precipitation component for the model. Lin said the historical record and climate models show that a warming climate increases the probability that extreme events like tropical cyclones will occur. By simulating what could happen in the future, these climate research projects provide data that government authorities and other entities can use to make informed decisions.

Jonathan Sury is a Columbia University researcher studying the varied public health impacts caused by petrochemical spills. In their research, the team will learn what chemicals are stored in the area and how spills of these chemicals could impact public health.

Sury said that the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill provides a good example of how petrochemical spills can impact public health. The spill caused people to develop rashes, asthma, eye and skin irritation and damage to bodily organs.

Sury’s health team will begin by reviewing large national datasets on environmental exposures and health impacts to determine if they give an accurate depiction of the data collected on these topics in local regions. The health team will create a data catalog of their own and will compare their findings with what is portrayed at the national level.

Sury said that petrochemical spills can create lots of stress for people. People affected by a spill may be worried about how the spill will impact their health, the health of their family, or their livelihood and how they will provide for their family.

The health team will establish working groups in both Baton Rouge and Houston to work with locals and gather information. The researchers will interview members of environmental justice organizations, community-based organizations, departments of health and other community members that are involved in environmental justice activism on their perceptions of various issues, like the impacts of manmade disasters or climate change.

Sury’s team will simulate possible health impacts using a system of models that will depict different scenarios based on the data collected on tropical cyclones and the durability of petrochemical storage tanks. The scenarios and their predicted health impacts will be available for the public to view on an online data hub.

Sury said he hopes the NAS project will lead to the creation of better disaster mitigation strategies in the future.

“Ultimately, I hope this does lead to mitigation efforts, I hope it does lead to adaptation efforts because, reality is, we are facing more and more severe and intense storms,” Sury said.

Correcting Climate Models

Current climate models face a challenge called “cold tongue bias.” This refers to the inability of climate models to accurately simulate an area of colder sea surface temperatures that has been observed in the central Pacific Ocean. While climate models show a warming climate in this area, observations show that the waters in the central Pacific are cooling.

MSU climate scientist Fosu said that the area where the cold tongue bias occurs is important to climate science because of its impact on the El Niño Southern Oscillation.

An El Niño occurs whenever warmer surface waters in the central Pacific move eastward towards the coast of Peru. These warmer temperatures influence atmospheric circulation, ultimately impacting temperatures and rainfall in the U.S.

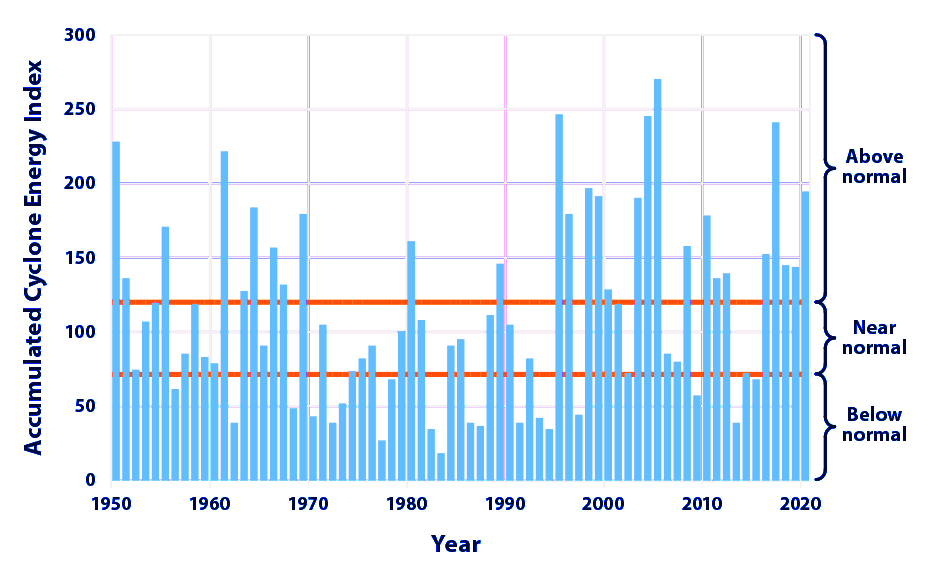

El Niño impacts the formation of tropical cyclones in the Atlantic Basin. Years with El Niño tend to produce less hurricanes as there is stronger wind shear, which is detrimental to hurricane formation. There is a greater chance for hurricanes during La Niña (when colder surface waters move eastward towards Peru), where there is less vertical wind shear and less atmospheric stability.

Two research projects between MSU, Stony Brook University and Columbia University are focused on correcting this bias in a U.S. National Science Foundation climate model and a U.S. Department of Energy climate model. The team will use these adjusted models to project how tropical cyclones in the Atlantic Basin will be impacted by climate change.

Fosu said that, while climate models have limitations, they are the best tool scientists have for predicting future changes in the climate. As researchers better understand the science behind our climate, and as computing power increases, climate models will improve.

Total annual Accumulated Cyclone Energy (ACE) Index values, which account for cyclone strength, duration and frequency, from 1950 through 2020.