“As I was walking across the street, she finally looked up and noticed me, but it was too late,” Hannah Harris said as she recalled the moments before she was struck by a vehicle while crossing Bully Boulevard. “Luckily, I was okay. I wasn’t really injured, but she decided to speed off.”

Harris is a junior business administration major at Mississippi State University who was walking her typical route to class earlier in March. However, embarrassment and bruises were all that Harris was left with after being struck by a car that ran straight through a crosswalk on campus, but she is considered a lucky one.

“I honestly panicked and was so embarrassed, and I was scared because how many other people has this happened to? I was glad it didn’t result any anything worse because I could have fell under the car and got ran over,” Harris said. “You know, then she just drove away.”

After repeated accidents within the last decade, Mississippi State acknowledged the risk pedestrians face on campus and implemented an enhanced gate system in 2022 to limit vehicle traffic and supplement the crosswalks. But accidents like the one Harris faced earlier this year still happen.

Not only do pedestrians face risks within Mississippi State’s campus, but community members in the city of Starkville are no strangers to these accidents either.

In 2017, former Mississippi State employee Jay Burrell was killed at the age of 54 while riding his bike along Highway 25.

Twenty-six-year-old Brittany Phillips was killed in 2019 while walking on Riviera Road in Starkville.

Just last year, an SUV fatally collided with 32-year-old Brittana Brewer who was walking along Highway 82 around 9 a.m. in late March.

Statistics from the United States Department of Transportation show that Mississippi was ranked as the third-highest state for car-related pedestrian fatalities and first in overall fatal car crashes per 100,000 people in 2020. In 2021, this statistic dropped for the Magnolia State, but 2022 recorded another increase in deaths within these two areas.

From 2018 to 2022, the city of Starkville recorded that nine pedestrians and three cyclists were killed within that five-year span.

While records and personal accounts show there are risks when traveling as a pedestrian, senior chemistry major Jennifer Greer expressed that even with putting the thought of risks aside, Starkville does not have a convenient route for pedestrians to get to their necessary destination without walking alongside the main highway — a route designed specifically for car traffic.

During her first three years at Mississippi State, Greer was without a car. She relied on the bus system and her friends’ kindness to get around, but Greer explained that walking has always been her favorite mode of transportation.

“I didn’t mind when I didn’t have a car because I actually like walking anyways,” Greer said. “I always walk to campus and around, and one time I tried walking to downtown. I was walking through neighborhoods and all that stuff, but I understand that people don’t want random people in their neighborhood. There were a lot of twists and turns to get safely to downtown, but I ended up having to call my roommate to pick me up, because I was like, ‘hey, I am not comfortable walking back home, please come get me.’”

As another advocate for a slower-paced, conservative form of transportation, MSU associate professor James Chamberlain said he prefers to travel using his bike.

Every weekday, Chamberlain loads up his two children, one sitting on the backseat of his tandem bike and the other on the tag-along attached to the back and pedals them to school.

“For the most part, my experiences of riding around town are positive,” Chamberlain said. “I find that people do give a lot of room when they pass and are courteous. When I take my kids to school, they even wave and encourage, so that’s really nice.”

Chamberlain did not express any level of fear about riding through Starkville on his bike; however, busy roads like Highway 12, with little room for cyclists, make it nearly impossible to get everywhere he needs to go.

Harris, Chamberlain and Greer acknowledged how not just them personally, but the entire community of Starkville could benefit from a protected route for pedestrians and cyclists to use for either recreation or transportation.

The city of Starkville has been reaching for a development that would accommodate this issue for nearly two decades.

Within the United States, there are an estimated 2,423 pedestrian trails that were converted from disused railroad tracks. Rails-to-Trails Conservancy is the organization that heads up the transformation of tracks into walking and biking trails for recreation or transportation — giving people an opportunity to safely get from point A to point B without relying on a car or worrying about vehicle traffic.

As an avid cyclist, Chamberlain described his experiences biking along several converted railroad tracks throughout the United States. He feels that Starkville could benefit from something similar.

“If we had a trail like this in town, I definitely think it would promote cycling and get people out to ride bikes in ways that they don’t feel comfortable doing now,” Chamberlain said. “But truly, I’ve been thinking how useful it would be for commuters. It would still be useful if it provides us with recreation, but it might make cycling a more viable alternative to a car.”

Acknowledging the need for a safe alternative to the busy highways, Mayor Lynn Spruill explained that she has been pushing for this conversion for the betterment of the Starkville community, but logistics and technicalities remain her biggest obstacle.

Canadian Pacific Kansas City railway company (CPKC) has been holding on tight to the ownership of the tracks in Starkville since the early 2000s, but for the rail conversion to begin, the tracks must be given to the city.

“Truly, I have been trying to touch base with CPKC and get them to release the track since 2005 when I first became involved in the city,” Spruill said. “So, all along I’ve been trying to get some movement or support or make some effort to try to get them to release it, respond or come visit us and tell us why.”

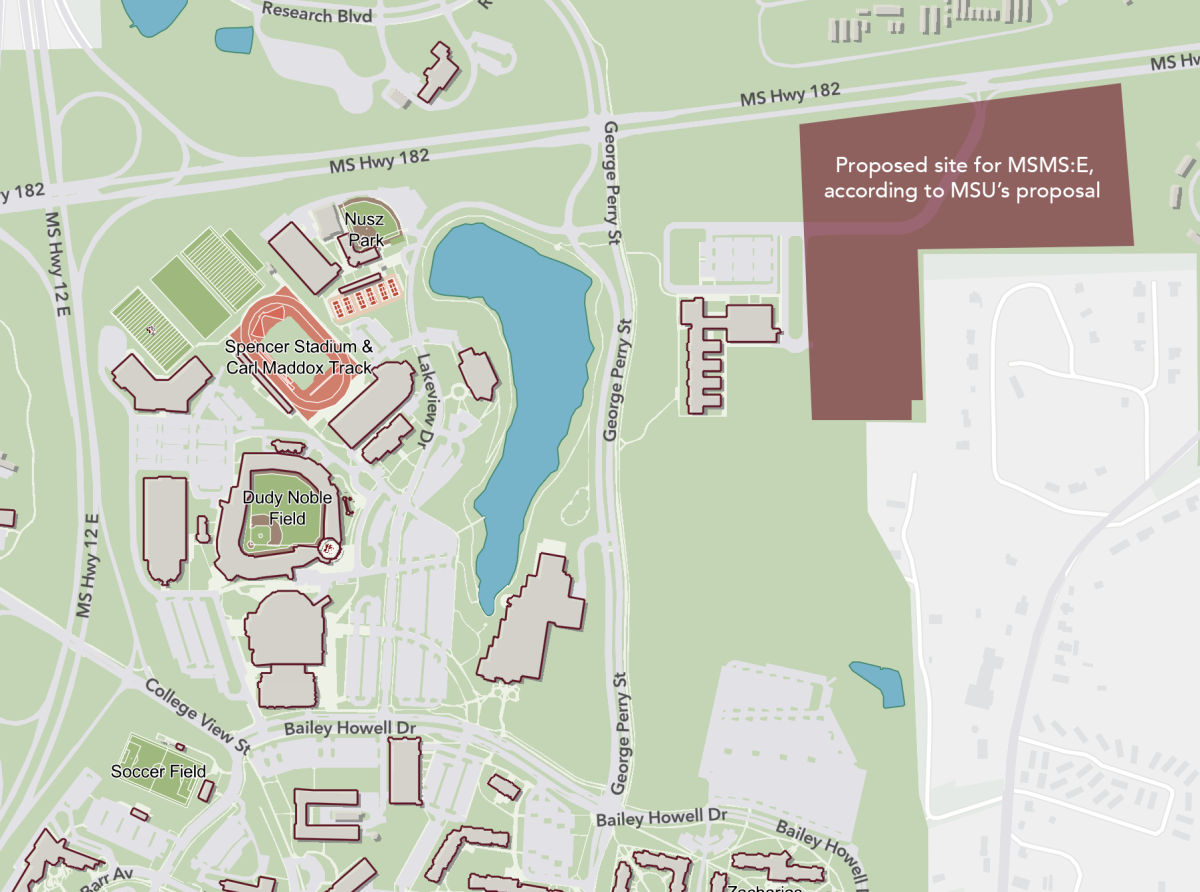

Along with an economic boost for the city, Spruill said she believes the trail could help alleviate the risks that pedestrians face while traveling on the same roads as vehicles. The tracks wind throughout Starkville, hitting various mainstays within the town and giving pedestrians a potential new option for getting to their necessary every day stops.

“While it’s a huge economic driver, I think it’s a quality-of-life issue. I think people would love to, you know, bike from the research park to even downtown.” Spruill said. “It’s about a six-mile run that you could jog on, walk on or bike on. And this isn’t just for recreation, it could be for transportation as well.”

Within the past decade, this potential new development has sparked chatter and interest among Starkville and surrounding communities, but the Rails-to-Trails conversion has no future in Starkville until the railroad company agrees to hand over ownership of the track to the city.

However, community members are becoming impatient for someone to make a move, and Harris said she empathizes with anyone who has ever been in a dangerous position as a pedestrian on a road dominated by cars.

“There’s a lot of instances in Starkville that people have been hit by cars, and some have even been killed. It was scary for me, and I even got the least of it. People just walk across the highway, but there’s no convenient way to do it in a safe manner. There has to be something different,” Harris said. “Not everyone has a car here, either. The buses are not great, and some people have to walk. There needs to be something in place to help people get around safely.”