Black Folk Art

On May 14, 2014, Jean-Michel Basquiat’s “The Undiscovered Genius of the Mississippi Delta” sold at Sotheby’s for a little under $24 million. It is a monumental work, a generous 15 feet long, covered in Basquiat’s famous chicken-scratch writing and love of anatomy, made up of five separate canvas panels. Considered by Sotheby’s as among Basquiat’s most political works, the painting offers a personal grievance and celebration of a great tradition of art from the South, raw and untrained.

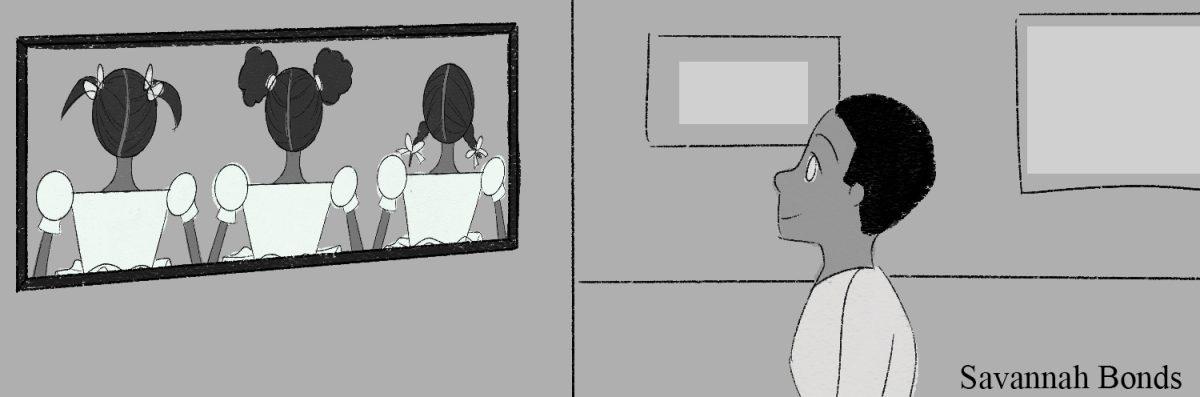

Parallel to Basquiat’s own body of work, painters in the Mississippi Delta have been creating folk art for generations while making use of unconventional mediums and written inscriptions, creating rich personal accounts and intimate recreations of life in the South. As we consider Black history this month, it would be criminal to fail to acknowledge southern Black people’s rich tradition of visual folk art, overlooked and undervalued by the art world but perhaps the most quintessentially American art movement to date.

Folk art is hard to define, largely because, according to Mamie Harmon of Britannica, the term was coined to differentiate so-called high art from that done by regular people, effectively written as a catch-all for any art done by someone who was not classically trained or living in a major art hub. Basquiat himself, for instance, was a wildly famous New York City painter but, due to his location, was not counted in the same genre as other folk artists despite the striking visual similarities between the art styles. The word is slowly coming into its own definition, though the official meaning is now art done by an artist who is, be it geographically or for any other reasons, somehow separated from the trends of the art world as a whole.

Folk art is often known for being made of whatever is lying around at the time. According to Chris Goertzen of the Mississippi Arts Commission, L.V. Hull, a Black artist from McAdams, Mississippi, spent her time creating “vernacular art yardscapes.” Unlike classical sculpture, Hull’s yardscapes are not made from raw material. Instead, Hull created works out of hubcaps, old shoes, ceiling fans, assorted boards and other accoutrement she could find. Her work is lively and chaotic, often featuring epitaphs painted in excited letters, surrounded by polkadots in vibrant shades. Her work also seems to speak to the soul of folk art; in that, when viewed by an inexperienced eye it looks a lot like garbage. In fact, it is made of garbage, and thus it is easily overlooked for its less than polished appearance. In reality though, much like the genre of art itself, when looked at longer, it speaks of the great joy and eccentricity of the artist herself, a deep and intimate exchanging of ideas straight from her mind to ours.

Southern folk art is also marked by the unconventional training of the artists who make it, most of whom never saw the inside of an art classroom. Peter Schjeldahl of The New Yorker details how Bill Traylor, among the most famous folk artists in the pantheon, started doing art while living on the streets of Montgomery, Alabama, drawing scenes inspired by the world around him — feral dogs, men in top hats passing by — taken live from scene to eye to board.

In an interview with WKNO FM’s Kacky Walton, Memphis, Tennessee-based folk painter N.J. Woods says she paints landscapes because her mother always sent her to play outside as a child, leaving nature to become the space she is most familiar with. One of her recent works features a night scape with a small blue house and the inscription, “Mama said, ‘If you can see the moon, you’re too late getting home.'”

That is the chief reason I love southern folk art: it is personal. And it is snapshots of small moments. It is visuals of real lives, shown without the edifice of high art. It is an artist pulling you aside to express to you a feeling or a memory without all the bells and whistles.

Southern folk art is wonderful for a myriad of reasons, from its vibrant visual style to its all welcoming community, but one reason worth noting is it is a movement which is still happening. The style is generations old but is still coming into its own as a genre. This coming year, as art shows reopen, go to a folk art show and watch. What you will witness at these festivals is art history unfolding in real time, a criminally overlooked community of Black artists writing the future of what American art looks like.